Design thinking is a phrase that’s recently shot into prominence across the globe. The creation of prestigious design thinking programs at institutions such as MIT and Stanford University has established its importance, and it’s become something of a buzzword.

But what exactly is design thinking? Its popularity means its importance is being widely recognized, but with popularity, there is always the risk of over-use and over-simplification.

Although we can’t promise an MIT standard of education, this blog post provides an in-depth breakdown of design thinking and some tips for hiring impressive design thinkers.

Design thinking demystified

Everybody talks about design thinking differently. To some, it’s an ideology; for others, it’s a process, and some people even think of it as a craft. Harvard Business Review has suggested we describe it as a social technology.

It can easily be all four. Which one is largely dictated by who is doing the design thinking and in what context. It is heavily based on the processes and methods that designers use to create and deliver innovative designs: It helps them make good things that people want to use.

Because of this, it is most frequently employed as an iterative process that can be used to approach the design of just about anything – the design-thinking method is repeated, systematically or flexibly, until a result or solution is achieved.

Despite its design-specific origins, it’s important to recognize that design thinking can be applied in any field. It has evolved to include engineering, architecture, and business – it’s relevant to any company that builds and delivers a product, experience, or service to its customers.

Design thinking is a solution-based approach to problem-solving

Focussing first and foremost on the humans for whom these products, experiences, and services are created, design thinking is a process that demands empathy and creativity. At its core, it is a way of solving problems by specifically empathizing with the person or situation you are problem-solving for.

We call this user-centric way of solving problems solution-based thinking. It focuses on finding and building solutions, rather than making problems and obstacles, and the reasons why they emerged, the focal point of problem-solving efforts.

Design thinking has 4 principles

Christoph Meinel and Larry Leifer of the Hasso-Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford University, the birthplace of design thinking, identified these four principles in 2010 in the first collection of research findings published by the institute.

The Human Rule

All design is social in nature. No matter the context, design thinking always comes back to the human-centric point of view. Technical problems must be solved in ways that satisfy human needs.

The Ambiguity Rule

Ambiguity is inevitable. It can’t be removed, and so experimentation is needed to understand and respond to as many interpretations as possible. Design thinkers must preserve ambiguity.

There is no chance for “chance discovery” if the box is closed tightly, the constraints enumerated excessively, and the fear of failure is always at hand. Innovation demands experimentation at the limits of our knowledge, at the limits of our ability to control events, and with freedom to see things differently.

Meinel and Leifer on the Ambiguity Rule in Understanding Innovation (2010)

The Redesign Rule

All design is redesign. Although social and technological conditions change all the time, basic human needs stay the same, and we only redesign the means of fulfilling these needs. Understanding how these needs have been met in the past is imperative to better estimating future conditions.

The Tangibility Rule

Making ideas tangible always facilitates communication. This refers directly to creating prototypes – according to Meinel and Leifer, prototypes are communication media. By this, they mean that prototyping enables design thinkers to collaborate constructively.

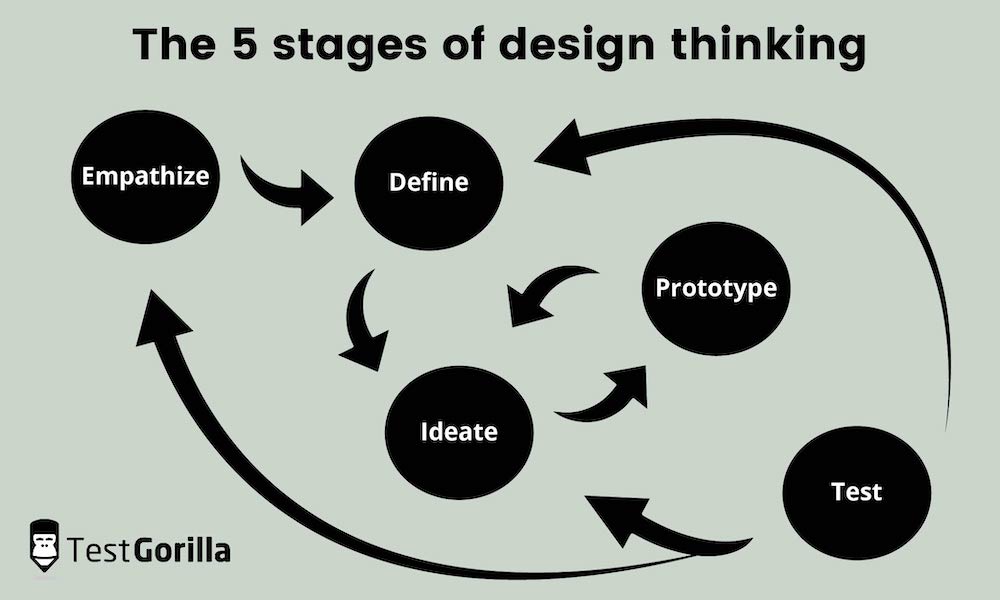

The 5 stages of design thinking

Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.

Herbert A. Simon (1966)

In 1969, the Nobel Prize laureate Herbert A. Simon outlined seven phases of design that influence modern-day design thinking. Simon’s work is still relevant; the fact that his definition of a designer remains popularly cited is a testament to this. But the Hasso-Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford proposes an updated and simplified five-step process.

1. Empathize

Empathy is the critical starting point for all design thinking. This stage is focused on research. Spend time getting to know your human users with the aim of understanding their wants, needs, and objectives as deeply as possible. Needs must be identified and understood before they can be addressed with effective solutions.

2. Define

This stage is dedicated to defining the problems identified in the first stage. Gather your findings and make sense of them by asking yourself questions about your users’ needs and problems.

Questions to ask yourself at the Define stage

What problems are my users encountering?

Are there any patterns?

Are these problems related to one another?

At the end of this stage, you should have a clear problem statement that frames in user-centered terms the problem you’ve identified and intend to create a solution for. It should appeal to a niche but also invite a flexible and creative approach.

One example of a problem statement might be: Students need one place where they can view freelance odd jobs near them at a glance. They need money but don’t have the time to commit to a job, and don’t know where to look for flexible work opportunities.

3. Ideate

Now you’ve identified, understood, and defined your problem, it’s time to ideate. This stage is all about coming up with ideas for potential solutions. It’s the most creative stage of the design-thinking process, and designers tend to hold ideation sessions to brainstorm ideas.

Diversity of thought is extremely valuable here. A successful ideation stage will incorporate as many perspectives and angles as possible. Design thinkers use many creative techniques to fuel idea generation. By provoking themselves into thinking laterally, they can step beyond obvious solutions and uncover areas of innovation.

Top 5 ideation methods

Brainstorming is the most common form of ideation and is best mixed with brainwriting, brainwalking, and braindumping.

Storyboarding can be used to illustrate user experiences in context to provoke discussion. It’s a good way of getting innovators to identify hidden needs by living out the customer’s experience.

Co-creation techniques bring together users and designers for ideation.

The SCAMPER technique involves using seven prompts – substitute (S), combine (C), adapt (A), modify (M), put to another use (P), eliminate (E), and reverse (R) – to ask questions about potential solutions.

Take a creative pause to interrupt your thoughts, walk away from what you’re thinking about for a while, and come back with some perspective.

At the end of this stage, you’ll have a portfolio of options to move forward with, prototype, and test.

4. Prototype

A prototype is a scaled-down mock-up of your potential products or solutions. These iterations can be used to interrogate ideas further and identify what might be missing, or what may need ironing out. Remember the Tangibility Rule: Making ideas tangible always facilitates communication.

5. Test

This stage is all about user testing. The solutions proven to be best in the prototyping phase are pulled together into one complete product that can then be tested in real life.

This is rarely the end of the process, since new problems that will push things back to the defining or ideating stages will likely surface during testing. User testing might even reveal oversights because of insufficient empathy with users, taking the design thinking-process back to the empathize stage.

Design thinking is not a linear process

Although these stages are followed in order to start with, and can be repeated iteratively until teams reach the best possible solution or product, to use design thinking to its full potential is to understand that it’s not a rigid or linear process.

The best design thinkers know when to hop back and forth between different stages to optimize products and solutions as much as possible. They also know that iteration is crucial. Ambiguity is also crucial, so ideas and prototypes will sometimes need to be formed and re-formed in multiple iterations before you reach an optimized solution that is worth investing in.

The best insights on HR and recruitment, delivered to your inbox.

Biweekly updates. No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Why is design thinking useful?

The beauty of design thinking lies in its flexibility

It demands both iteration and adaption, making it an effective way to approach new or ill-defined problems as well as familiar problems that need new and innovative solutions. Basically, it is useful because of how widely it can be applied.

With these five stages as a general outline, a huge variety of businesses, organizations, and teams can use design thinking for an equally huge variety of projects, adapting the framework as it suits them.

Creative processes can be daunting because they are wide open to possibilities. Design thinking, whether implemented as a method, adopted as a mindset, or honed as a craft, enables a manageable and constructive approach that at once embraces and controls these possibilities.

Design thinking has the potential to do for innovation exactly what TQM (Total Quality Management) did for manufacturing: unleash people’s full creative energies, win their commitment, and radically improve processes.

Jeanne Liedtka for HBR, ‘Why Design Thinking Works’ (2018)

Design thinking can tackle human biases

At its core, design thinking is about incorporating as diverse a range of views and experiences as possible to deepen our understanding of users, their problems, and the possible solutions. Human biases can thwart creativity by doing the opposite, because they render certain voices less important or dismiss them entirely.

Because it has the reverse effect of unconscious bias, design thinking is a great way for organizations to combat bias when they’re developing solutions. It works because it recognizes organizations as collections of people who are all different, and have varying emotions, motivations, and responses to things.

Involving users and other stakeholders, as well as designers and innovators, puts the emphasis on dialogue, engagement, and empathy. Definitions of problems are broadened, and the possibilities for innovative solutions broaden with them.

Which jobs require design thinking?

With the rise of design-thinking degree programs, a design-thinking job genre has emerged to match. People who commit to design-thinking education in this way can build the knowledge and expertise to become design-thinking consultants, analysts, or specialists. They can also go into design research, strategy, or management.

Amazingly then, design thinking can be a whole career in itself. In April 2022, there were 20,162 LinkedIn job postings for design strategists worldwide, more than 5,000 of which were remote.

There will be a far longer list of postings for jobs where design thinking doesn’t necessarily define the role in question but is still crucial to it. These jobs might be in almost any industry or sector, so a list could easily be twice as long as this blog post. To make things easier for you, we’ve pulled together a few of the most relevant ones and divided them according to how important design thinking is for the role.

Design thinking is vital for:

Designers in any industry

Brand managers

Product managers and developers

UX/UI designers and specialists

Solution delivery managers

Senior front-end developers

Architects and planners

Design thinking is useful for:

Entrepreneurs and business owners

Operations engineers and managers

Business analysts

Administrative roles

Patient engagement specialists

Managers in hospitality and retail

Customer service representatives

Hiring for design-thinking skills

No matter your job description, design-thinking skills are useful to have. But some roles just can’t do without it. If you’re a recruiter or hiring manager and you’re seeking candidates for design-related jobs, this section is for you.

You should also take a look at our guide to design thinking interview questions that actually test problem-solving.

As our lives become increasingly digital, the quality of digital user experience is more important now than ever. This is why so many of those design-strategist jobs are advertised as remote. In true design-thinking style, companies with digital products have access to a diverse pool of potential employees from all around the world.

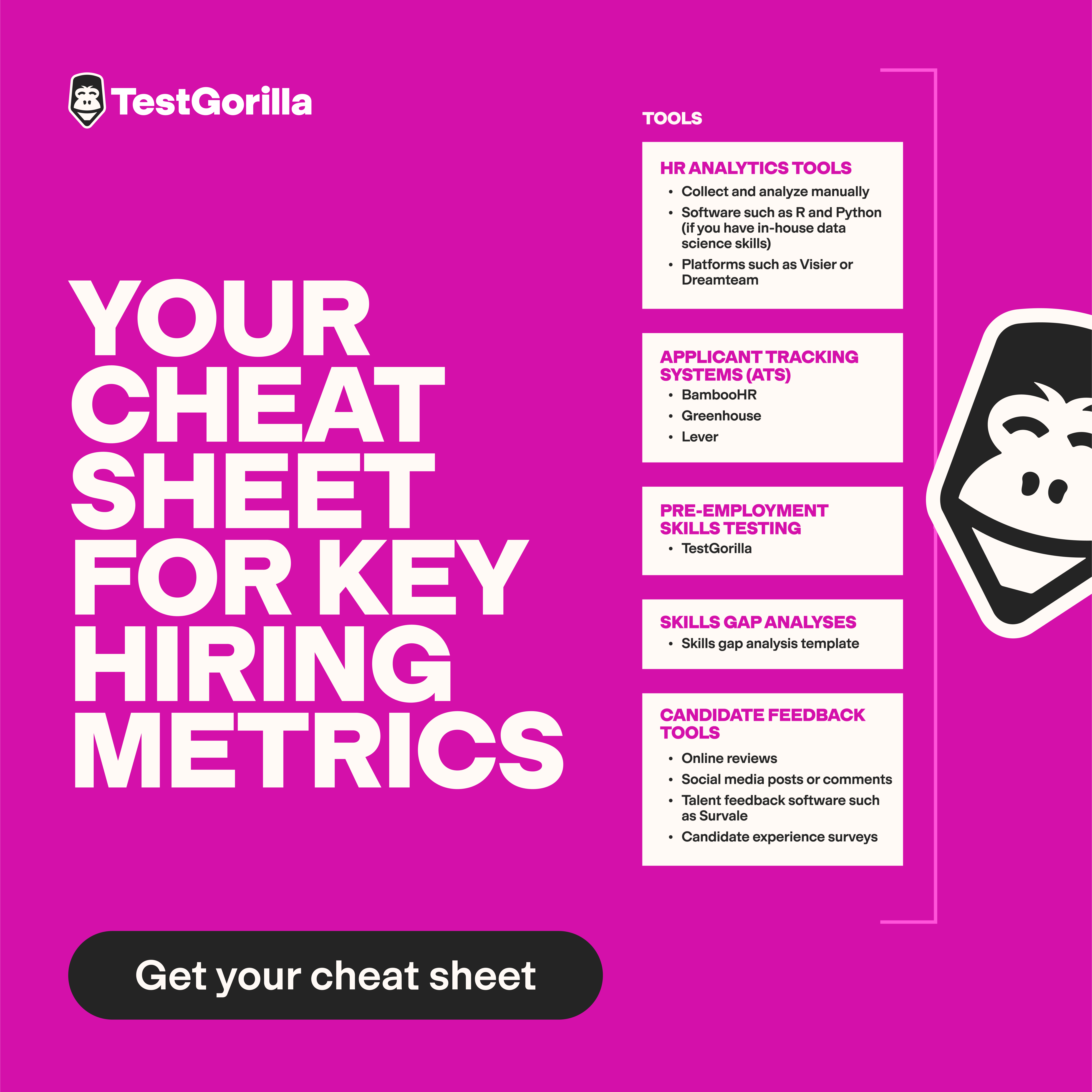

Use our UX/UI design test to hire the best design thinkers

In any role that requires a grasp of UX/UI design skills and principles, design thinking is key. The best way to evaluate design thinking skills is to give candidates a skills test at the top of the recruitment funnel. This way, you get a reliable indicator of their design-thinking proficiency that you simply can’t ascertain from a CV alone.

User experience (UX) design ensures that users don’t simply get something done using your product but actually enjoy the experience of getting from point A to point B. User interface design (UI) ensures that the screen visually communicates the path to get users from point A to point B without friction or doubt.

TestGorilla

TestGorilla’s UX/UI design test covers the following skills:

Design thinking

Wireframing and UI design

Prototyping and testing

Developer handoff

Candidates who perform well on the test will have a robust understanding of design and user issues and will be familiar with and competent in the design process.

If you’re looking for UX/UI-related job candidates with design-thinking skills, TestGorilla can help simplify your recruitment journey. Sign up today for access to the UX/UI design test and more through our ever-growing, science-backed test library.

You've scrolled this far

Why not try TestGorilla for free, and see what happens when you put skills first.