How early education impacts the workforce – and what employers can do to improve it

We’ve all heard the statistic that 90% of brain development happens before age five.

While this claim is hard to verify, researchers do agree that the first eight years of a child’s life have a strong role in determining their future success.[1]

This makes sense. Early childhood is when we develop many of the basic skills we need for not only school, but also for our later professional lives: reading comprehension, problem-solving, and communication are among them.

But what is the state of early education around the world, and how is this reflected in the trends we’re seeing in the labor market?

Perhaps even more importantly, what can you as an employer do to improve it?

Although there are many factors out of your control, you are responsible for dozens, if not hundreds or thousands, of workers and their families. You are, therefore, uniquely positioned to impact the early experiences of children – and the future of the workforce.

In this blog, we look at obstacles to early education and the effect this is having on the workforce, plus what you can do as an employer to break down these barriers.

Table of contents

- What does early childhood education (ECE) mean?

- What impact does good early childhood education have on the lives of children?

- Barriers to early childhood education around the world

- What problems does lack of access to early childhood education cause in the workplace?

- 4 ways skills-based organizations can improve access to early childhood education

- Change starts with you: Switch to skills-based hiring to promote equality of opportunity

- Sources

What does early childhood education (ECE) mean?

Early Childhood Education (ECE) is usually defined as education for children up to the age of eight. It encompasses different types of schooling, including:

Preschool or nursery

Kindergarten

Elementary or primary school

Different countries around the world start compulsory early childhood education at different ages, ranging from as young as three to as old as eight.

For instance, in France and Hungary, compulsory education starts at three years old, whereas in the United States, this can be anywhere from five to eight, depending on your state.[2]

Until children can enroll in public free education, options for childcare are limited, but ways that parents might kick-start early childhood education include:

Hiring an au pair or babysitter

Enrolling in a daycare educational program

Preparing learning activities yourself

The goal of early childhood education is to lay a strong foundation for later learning and development by nurturing all key skills areas:

Physical, including motor skills and fitness

Cognitive, such as problem-solving, numerical reasoning, and reading

Emotional, such as emotional regulation and the ability to empathize with others

Social skills, laying the foundations for many of the soft skills they will use throughout their academic and professional lives

There are many methods for nurturing these skills, including the Montessori method, which allows children to direct their own learning and encourages growth through curiosity.

In this blog, we chiefly focus on early childhood education, but a lot of what we discuss is also applicable to education before high school.

How is early childhood education different from early childhood development (ECD)?

Early childhood education is closely related to (and easily confused with) early childhood development (ECD).

ECD accounts for the development that occurs before children start compulsory education, usually around the age of four. This might include attendance to educational institutions, such as a preschool, but doesn’t specifically refer to educational environments.

For many children, early childhood development happens at home with their family. This means that although early childhood education can be a part of early childhood development (for example, if a child is enrolled in preschool) the two terms aren’t always synonymous.

What impact does good early childhood education have on the lives of children?

There is ample evidence that a positive experience in early childhood education is a strong predictor of positive outcomes later in life.

Influential 2009 research showed that children who were enrolled in ECE performed better in society and were less likely to have interactions with law enforcement later on.[3]

However, childhood experiences at this age are also determined by their home lives. For example, in two-parent households where children are raised by a mother and a father, the roles their parents assume can impact the skills their children develop.

These roles are invariably influenced by societal gender norms, and researchers have observed the impact of gender on the development of reading skills of children.

Fathers are less likely to read themselves, so, many children grow up with fewer male role models for reading.

Fathers of sons are also less likely to read to them than fathers of daughters; men and teenage boys are also more likely than women and girls to choose other entertainment activities like gaming instead of reading.[4]

These gendered norms may also be exacerbated in households with a single parent or parents in a same-sex relationship, but there is limited research into this area.

ECE is a key time for mindset formation – in other words, this is the period when children will cement attitudes to learning and their self-image when it comes to their intelligence, creativity, and ability to problem solve.

The effects of child mindsets have been shown to eclipse even factors like home environment in predicting school achievement down the road.[5]

The best insights on HR and recruitment, delivered to your inbox.

Biweekly updates. No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Barriers to early childhood education around the world

Clearly, early education is very important to set children on the right path. And yet, in many parts of the world, enrollment in ECE isn’t high at all.

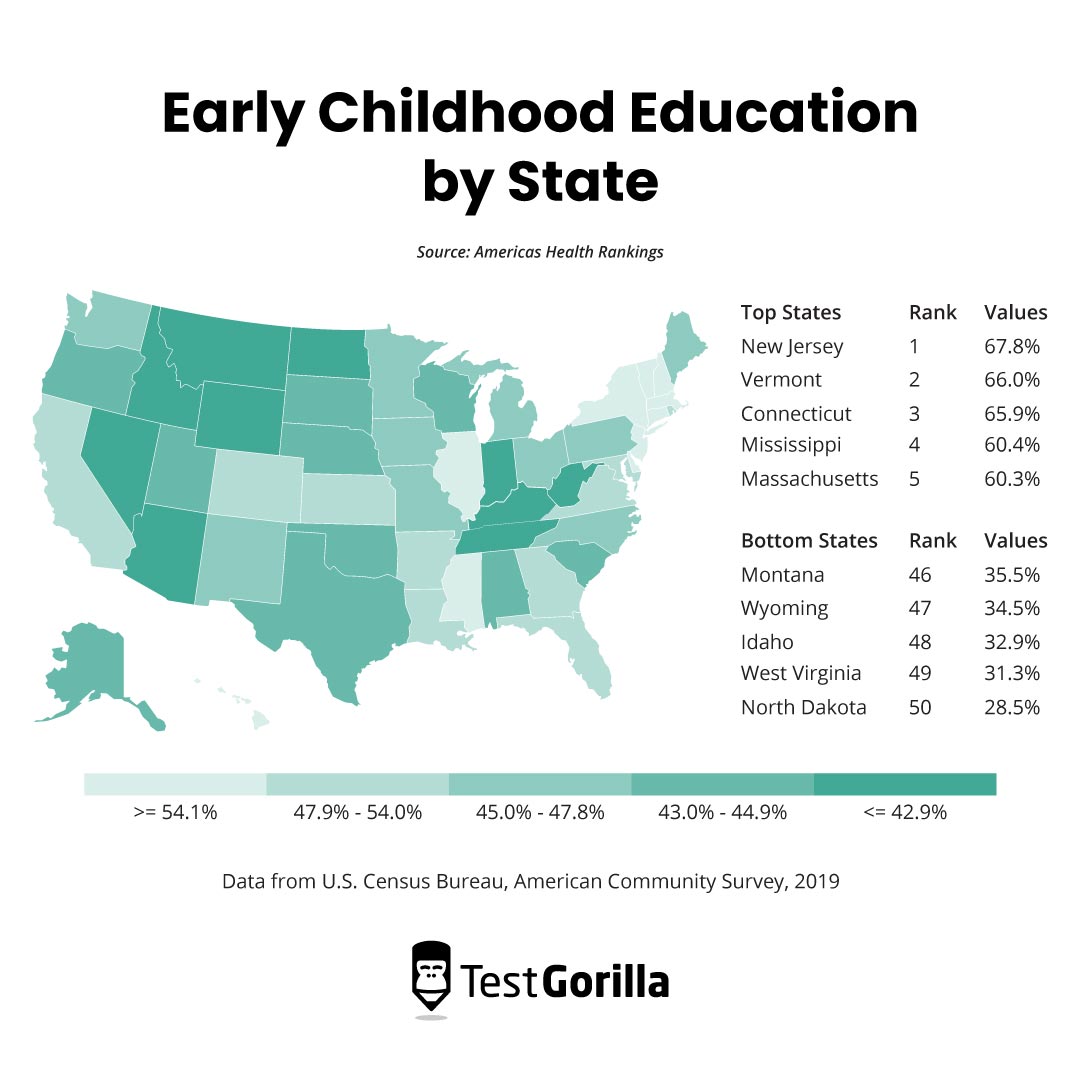

ECE enrollment varies massively even within the United States, with North Dakota having the lowest enrollment in ECE at just 28.8% of children aged 3-4. The figures for five-year-olds are higher, at around 63% overall, but this is still low – and lower than before the pandemic.[6]

There are three key factors that cause this variance:

Lack of investment from governments

It makes sense that the countries that invest the most in ECE have the highest enrollment. This is because higher government investment usually equates to a higher quality of learning and lower barriers to entry.

This often produces better outcomes later in early education.

Access to ECE is linked to better educational attainment in middle school. Students who had attended an early childhood education institution scored on average 27 points higher on PISA tests than students who hadn’t.

These are tests of a 15-year-old’s ability to apply reading, mathematics, and science skills to real-life problems. The difference in scores equates to the knowledge gained from more than six months of schooling in early childhood.

Lack of affordable childcare options

A lack of subsidized ECE usually means a scarcity of affordable childcare options.

In countries that are members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), childcare costs approximately 15% of the average household’s earnings. This is even higher in other areas of the world.[7]

Country | % of earnings spent on childcare (single parent) | % of earnings spent on childcare (two parents) |

Chile | 58.52% | 29.26% |

Netherlands | 56.73% | 28.36% |

Turkey | 55.56% | 27.78% |

Colombia | 50.32% | 25.16% |

United Kingdom | 47.65% | 23.82% |

Hungary | 30.78% | 15.39% |

United States | 26.09% | 13.04% |

Germany | 12.49% | 6.24% |

Finland | 12.17% | 6.08% |

Norway | 11.02% | 5.51% |

Iceland | 8.71% | 4.36% |

Sweden | 5.24% | 2.62% |

Naturally, low-income households are the hardest hit by this issue because they can’t afford many early childcare options, nor can they usually afford in-home care. This limits opportunities for these children to access ECE.

Instability at home

Finally, instability within the family structure can be a barrier to early childhood education. Research shows that the most influential factors in a child’s learning are:

Their home learning environment

The level of chaos in their household

The warmth of their relationship with their parents

Positive experiences in these areas were all associated with better educational performance later on.[8]

Parental disengagement isn’t always a marker of apathy, however, but can be caused by structural issues. In many low-income families and those living in poverty, parents don’t have time to engage deeply with early education because their time and energy are taken up with work.

Parents with better-paying jobs are more likely to have free time and energy to not only invest in their children’s early education but also engage personally with their development.

This is likely why parental income has been proven to have an even stronger effect on a child’s success than education alone.

This carries over to economic differences along racial lines. Studies show that equalizing parental income between Black families and White families was more powerful than equalizing later education in improving the career outcomes of children.[9]

These studies indicate that access to high-quality early childcare, often funded by the parents’ incomes, increases readiness for school and narrows the “achievement gap” by half.[10]

This leaves us with two solutions: Either equalize the incomes of the lowest-paid working parents or widen access to early childhood education regardless of income level. Either way, access to ECE is massively important for outcomes later in a child’s life.

What problems does lack of access to early childhood education cause in the workplace?

The foundation for educational inequality is laid long before many children even set foot in school, and this has far-reaching consequences.

Studies show that children are significantly less likely to graduate high school if they don’t attend ECE.[11]

Those from low-income backgrounds who had at least two years of high-quality ECE before the age of five were significantly more likely to graduate college. They also had higher salaries at age 26.[12]

But how do these individual disadvantages impact businesses? There are three key effects.

1. A lack of diversity

As we’ve seen, one of the main ways a lack of access to quality ECE impacts children is that they are less likely to graduate high school and proceed to higher education.

We also know that children from low-income families have less access to ECE, leading to the phenomenon by which just one-fifth of students from low-income families make it to college.[13]

Thanks to the prevalence of four-year degree requirements in many job postings, this introduces socioeconomic bias into recruitment – but that’s not all.

Racial disparities in the education system further exacerbate these inequalities. Children of color, particularly those from low-income backgrounds, are significantly more likely to be disciplined by educators, despite exhibiting the same behaviors as their White classmates.

Their punishments are also more likely to be severe, such as suspension or expulsion, with some studies suggesting this even starts in early childhood education.[14]

It’s no surprise, then, that 76% of African Americans and 83% of Hispanic workers lack a four-year college degree, compared to 56% of Asian Americans and 37% of non-Hispanic White Americans.[15]

Clearly, the educational inequality that begins in early childhood education creates a domino effect that leads to a lack of diversity in the workplace, contributing to the significant “degree gap” which has appeared in many roles.

The degree gap refers to the phenomenon by which four-year degrees are required for roles that formerly did not need them, even when there have been no changes in the skill requirements.

An example of this in action comes from 2015. That year, 67% of production supervisor job postings asked for a college degree, while only 16% of then-employed production supervisors had one.[16]

2. Skills shortages

So far, we’ve seen that the continuing use of degree requirements in hiring extends the influence of early childhood education inequality into the professional sphere. It also contributes to perceived skills shortages.

A skills shortage occurs when a skills gap (the lack of a specific skill within an organization) is also present on a wider scale, such as in an industry or a geographical region. In 2022, three-quarters of companies worldwide reported talent shortages, the highest number in 16 years.[17]

Skills shortages are linked to inequality in ECE because, as we’ve seen, marginalized and poor children are less likely to gain college degrees. This does not mean, however, that they are less capable of obtaining valuable skills – for example, through on-the-job training.

These workers are known as STARs, or workers “skilled through alternative routes.” An Opportunity@Work report has shown that, despite being hidden from many roles, lots of STARs do possess the skills required for so-called “higher skill” roles, especially in soft skill areas.[18]

Degree requirements, then, hide the valuable skills available from marginalized people in the workforce and enhance the damage that skills gaps are doing to employers.

This damage is substantial. One Betterworks report found that many organizations are taking longer to fill roles and paying out higher starting salaries thanks to the bargaining power skills gap hands to candidates.

3. Less innovation

The dual effects of a lack of diversity in the workforce and the presence of skills shortages in the talent pool – both of which, we can see, have their roots in unequal access to early childhood education – lead to a lack of innovation.

Not having the requisite skills for a role obviously hinders business progress, and Deloitte research shows that diversity of thinking increases innovation at organizations by as much as 20%.

Some studies even suggest specific benefits to hiring those who have been discriminated against in education and beyond.

The presence of “grit” in candidates – in other words, the experience of having to overcome obstacles and demonstrate resilience – has been linked to better job performance.[19]

The transformative powers of diversity are reflected in the revenue of companies that lead their industries in terms of diversity.

Those in the top quartile for racial and ethnic diversity are 35% more likely to perform above average for their industry. Those in the top quartile for gender diversity are 15% more likely to do so.[20]

What’s more, the relationship between diversity and financial performance is only getting stronger year on year.

4 ways skills-based organizations can improve access to early childhood education

We’ve seen that many of the urgent issues organizations are facing in 2023 can be traced back to educational inequality and particularly children’s early experiences of education.

But what can you, as an employer, do to change this?

Here are four key strategies.

4 ways to improve access to early childhood education: Summary table

Eager to be the change you need in your workforce? Here’s a quick summary to get you started.

Ways to improve access to early childhood education | Example actions |

Invest directly in early childhood education initiatives | Give employees a number of paid volunteering days a year to spend working with an early education charity |

Supporting families in the workplace | Equalize parental leave, not just for men and women, but across your whole workforce |

Increase diversity with skills-based hiring | Throw out degree requirements and use skills testing to screen candidates |

Increase gender diversity, particularly in HEAL roles | Run employment campaigns spotlighting current male workers |

1. Invest directly in early childhood education initiatives

The most effective way for employers to affect the quality of early childhood education is to donate to or directly sponsor ECE initiatives. For example, you might fundraise for free childcare or sponsor training for people to run ECE centers.

You’ll likely see a direct benefit from this investment. The National Forum on Early Childhood Policy and Programs found that high-quality ECE programs yielded $4-$9 for every $1 invested in them.[21]

You might also raise awareness by working with charities relevant to early education, such as Theirworld.

Theirworld is a charity currently urging governments to allocate 10% of education budgets and humanitarian aid for education to go to early childhood teaching. This would be an increase from the 1% of aid currently spent on pre-primary education.[22]

There are many ways you could apply this.

For example, you can introduce volunteering as a wellbeing initiative, giving employees a certain amount of paid leave per year to pursue charity work. This might be with a partner of their choice or a nominated early education charity.

As well as addressing a real business need, this is also an opportunity to demonstrate your commitment to your organizational values and to help employees connect with their community.

An example of an existing initiative like this comes from Salesforce. The company gives employees seven paid days of volunteering per year and even facilitates skills-based volunteering through its Impact Exchange.

This is a pro bono program through which nonprofit and education organizations can access Salesforce employees’ skills for additional projects on the platform. They simply upload their projects and select the most useful skills from the pool of volunteers.

2. Supporting families in the workplace

Another direct way to influence children’s early childhood education is to support working parents within your organization.

There are many ways you might do this. One of the most effective is to offer paid parental leave for all parents – fathers as well as mothers. This is a more inclusive practice that allows for more equal distribution of parenting roles in mixed-gender partnerships.

You should also, where possible, extend these policies to include all workers, not just your office workers. This means that all parents, regardless of their role in your company, are able to earn well and flexibly enough to afford decent childcare options.

You might even consider providing these options yourself. More and more employers are providing in-office childcare for children below the age of compulsory education. A famous example is Patagonia, whose chief human resources officer says he considers childcare to be a “bedrock employee benefit.”[23]

You’ll reap the rewards sooner than you might expect. One 2020 study found that organizations that invested in employee families exhibited 5.5 times more revenue growth thanks to innovation gains, better retention, and increased productivity.

Of course, inclusivity is more than just a growth engine for businesses. By allowing parents to remain in the workforce, you’re providing stability and role models for their children and are thereby provoking real change.

3. Increase diversity with skills-based hiring

So far, we’ve focused on how you can make changes for children right now. However, if we wait for today’s 4 to 11-year-olds to begin employment, we’ll be waiting at least a decade.

We need more immediate action, and that means removing the barriers for workers who have already been held back by their early childhood education experiences.

One way to do this is with skills-based hiring – in particular, removing outdated degree requirements from job ads.

This is a growing movement known as the “degree reset,” in which increasing numbers of employers are throwing out degree requirements in favor of more direct, objective screening measures like skills testing.

Unlike degree requirements, which are only a proxy for skills, online skills assessments directly measure a candidate’s capabilities regardless of where they gained those skills from. This helps STARs tear down the “paper ceiling” and access roles from which they were previously barred.

The potential impact here is clear. By leveling the playing field with skills-based hiring, you provide parents who aren’t college-educated with the opportunity to progress into higher-skill roles.

This firstly improves their family’s material conditions and stability. We’ve already seen the positive change this can bring for Black families.

As we said above, you’ll also provide their children with stability, as well as role models for what they could one day achieve. This creates not only present change but future change, too.

4. Promote gender diversity, particularly in HEAL roles

Finally, in addition to equalizing parental leave policies, you should also consciously pursue gender diversity on your teams, particularly if you’re in a field that’s dominated by one gender.

One example is “pink collar jobs.” These are roles such as nurses, nail technicians, and customer service assistants that see mainly female applicants and employees.

Many of these fall under the category of HEAL roles: Jobs in Health, Education, Administration, and Literacy (often thought of as the opposite of STEM: Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math).

Increasing gender diversity in these industries affects early childhood education by presenting children with a diverse range of role models for what they might grow up to become.

This has many benefits for child wellbeing. Firstly, adolescents who have grown up in countries with high levels of gender equality report higher life satisfaction than their peers on the other end of the spectrum.[24]

Secondly, for children growing up in two-parent households with a father and mother, gender diversity across a range of industries would equalize the value of men’s and women’s labor, making it more possible for parents to be equally involved in childcare.

In HEAL industries that deal directly with children, the effect of gender diversity can be especially direct.

Just more than 25% of public school teachers are men today, compared to 33% in 1980.[25,26]

And yet, Finnish research suggests that a more gender-balanced teaching staff brings benefits for all students.[27]

Clearly, promoting gender diversity in these roles can directly impact children’s early education experiences.

Achieving gender diversity in these industries is easier said than done because many such fields suffer from a gender application gap as well as bias within the recruitment process.

However, skills-based hiring is a start, especially in male-dominated industries. A study of more than 2,000 successful job applicants found that the number of women hired into senior roles increased by almost 70% when skills-based methods were used.[28]

In female-dominated industries, an overall disintegration of the gender binary is needed to help more men into HEAL roles which directly impact early education.

You might start this work by designing outreach programs for men with adjacent skills that would be useful in HEAL. You might also run employment campaigns specifically targeted at men, reframing the skills required for HEAL roles or spotlighting male workers.

Change starts with you: Switch to skills-based hiring to promote equality of opportunity

Ultimately, the problem of access to early childhood education is much bigger than any one employer or even any one industry.

However, employers are well-placed to influence change within their own organizations – and, by so doing, push forward much-needed conversations.

To get started with the strategies laid out above, read our blog about how to implement skills-based hiring practices.

To learn more about how the education system influences organizations, read our blog about how education can pave the way for skills-based learning.

Or, if you want to start hiring STARs and counteract the negative impacts of bad ECE experiences, use our Problem Solving test to hire the best.

Sources

Robinson Lara, et al. (July 28, 2017). “CDC Grand Rounds: Addressing Health Disparities in Early Childhood”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6629a1.htm

“Primary School Starting Age”. (2022). WorldBank. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/se.prm.ages?view=map

Heckman, James, et al. (2009). "The Rate of Return to the High/Scope Perry Preschool Program". NBER. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/15471.html

Auxier, Brooke, et al. (December 1, 2021). “The gender gap in reading: Boy meets book, boy loses book, boy never gets book back”. Deloitte Insights. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/technology/technology-media-and-telecom-predictions/2022/gender-gap-in-reading.html

Mourshed, Mona; Krawitz, Marc; Dorn, Emma. (September 22, 2017). “How to improve student educational outcomes: New insights from data analytics”. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/how-to-improve-student-educational-outcomes-new-insights-from-data-analytics

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). “Enrollment Rates of Young Children”. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cfa/enrollment-of-young-children

“Childcare support”. (April 2022). OECD Family Database. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3-4-Childcare-support.pdf

Melhuish, Edward; Gardiner, Julian. (February 2020). “Study of Early Education and Development (SEED): Impact Study on Early Education Use and Child Outcomes up to age five years”. UK Department for Education. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/867140/SEED_AGE_5_REPORT_FEB.pdf

Akhlagipour, Golnoush; Assari, Shervin. (December 7, 2020). “Parental Education, Household Income, Race, and Children’s Working Memory: Complexity of the Effects”. Brain Sci. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7762416/

Pianta, Robert, et al (October 5, 2021). “Invest in programs that boost children’s learning and development”. Brookings. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/education-plus-development/2021/10/05/invest-in-programs-that-boost-childrens-learning-and-development/

McCoy, Dana, et al. (November 2017). “Impacts of Early Childhood Education on Medium- and Long-Term Educational Outcomes”. Educ Res. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6107077/

Bustamante, Andres, et al. (2022). “Adult outcomes of sustained high-quality early child care and education: Do they vary by family income?”. Child Development. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cdev.13696

Fry, Richard; Cilluffo, Anthony. (May 22, 2019). “A Rising Share of Undergraduates Are From Poor Families, Especially at Less Selective Colleges”. Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/05/22/a-rising-share-of-undergraduates-are-from-poor-families-especially-at-less-selective-colleges/

“Study Furthers Understanding of Disparities in School Discipline”. (June 14, 2022). National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/research-highlights/2022/study-furthers-understanding-of-disparities-in-school-discipline

“Highest Educational Levels Reached by Adults in the U.S. Since 1940”. (March 30, 2017). US Census Bureau. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/cb17-51.html

Fuller, Joseph; Raman, Manjari. (October 2017). “Dismissed by Degrees”. Harvard Business School. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/dismissed-by-degrees_707b3f0e-a772-40b7-8f77-aed4a16016cc.pdf

“Navigating with the STARs: Reimagining Equitable Pathways to Mobility”. (2021). Opportunity@Work. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://opportunityatwork.org/our-solutions/stars-insights/navigating-stars-report/navigating-with-the-stars-report-download/

“The Talent Shortage”. (2022). ManPowerGroup. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://go.manpowergroup.com/talent-shortage

Gonlepa, Miapeh; Dilawar, Sana; Amosun, Tunde (2023). “Understanding employee creativity from the perspectives of grit, work engagement, person organization fit, and feedback”. Frontiers in Psychology. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1012315/full

Hunt, Dame Vivian; Layton, Dennis; Prince, Sara. (January 1, 2015). “Why diversity matters”. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/why-diversity-matters

“High Return on Investment (ROI)”. The Center for High Impact Philanthropy. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.impact.upenn.edu/early-childhood-toolkit/why-invest/what-is-the-return-on-investment/

“Early learning can build the skills young people need for jobs of the future”. (July 15, 2019). Theirworld. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://theirworld.org/news/how-early-learning-can-build-skills-youth-need-for-future-work/

Anderson, Bruce M. (September 10, 2019). “Why Patagonia CHRO Dean Carter Sees Onsite Child Care as a Bedrock Benefit”. LinkedIn Talent Blog. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.linkedin.com/business/talent/blog/talent-engagement/why-patagonia-offers-onsite-child-care

de Looze, Margaretha, et al. (2018). “The Happiest Kids on Earth: Gender Equality and Adolescent Life Satisfaction in Europe and North America”. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/123759/1/10.1007_2Fs10964_017_0756_7.pdf

“Teacher demographics and statistics in the US”. (2022). Zippia. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.zippia.com/teacher-jobs/demographics/

Ingersoll, Richard; Merrill, Lisa; Stuckey, Daniel. (April 2014). “Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force”. Consortium for Policy Research in Education. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://cpre.org/sites/default/files/workingpapers/1506_7trendsapril2014.pdf

“Young children may benefit from having more male teachers”. (June 30, 2022). The Economist. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2022/06/30/young-children-may-benefit-from-having-more-male-teachers

Sundaram, Khyati. (March 13, 2022). “‘Skills-based’ hiring driving 70% increase in senior roles for women hired”. The HR Director. Retrieved June 23, 2023. https://www.thehrdirector.com/business-news/diversity-and-equality-inclusion/skills-based-hiring-drives-a-70-increase-in-the-number-of-women-hired-for-senior-roles/

You've scrolled this far

Why not try TestGorilla for free, and see what happens when you put skills first.