How the focus on skills in hiring is driving the degree “reset” – and where universities go from here

One of the most controversial calls to action of skills-based hiring is for employers to ditch the typical requirement for a university degree and tear the paper ceiling.

Four-year degree requirements have been around for what feels like forever, but they’re not a good predictor of job success.

An analysis of 26 million job postings found that college graduates had lower levels of engagement at work and a higher rate of turnover.[1]

Even highly technical skills like data science don’t necessarily require a university degree to learn them.

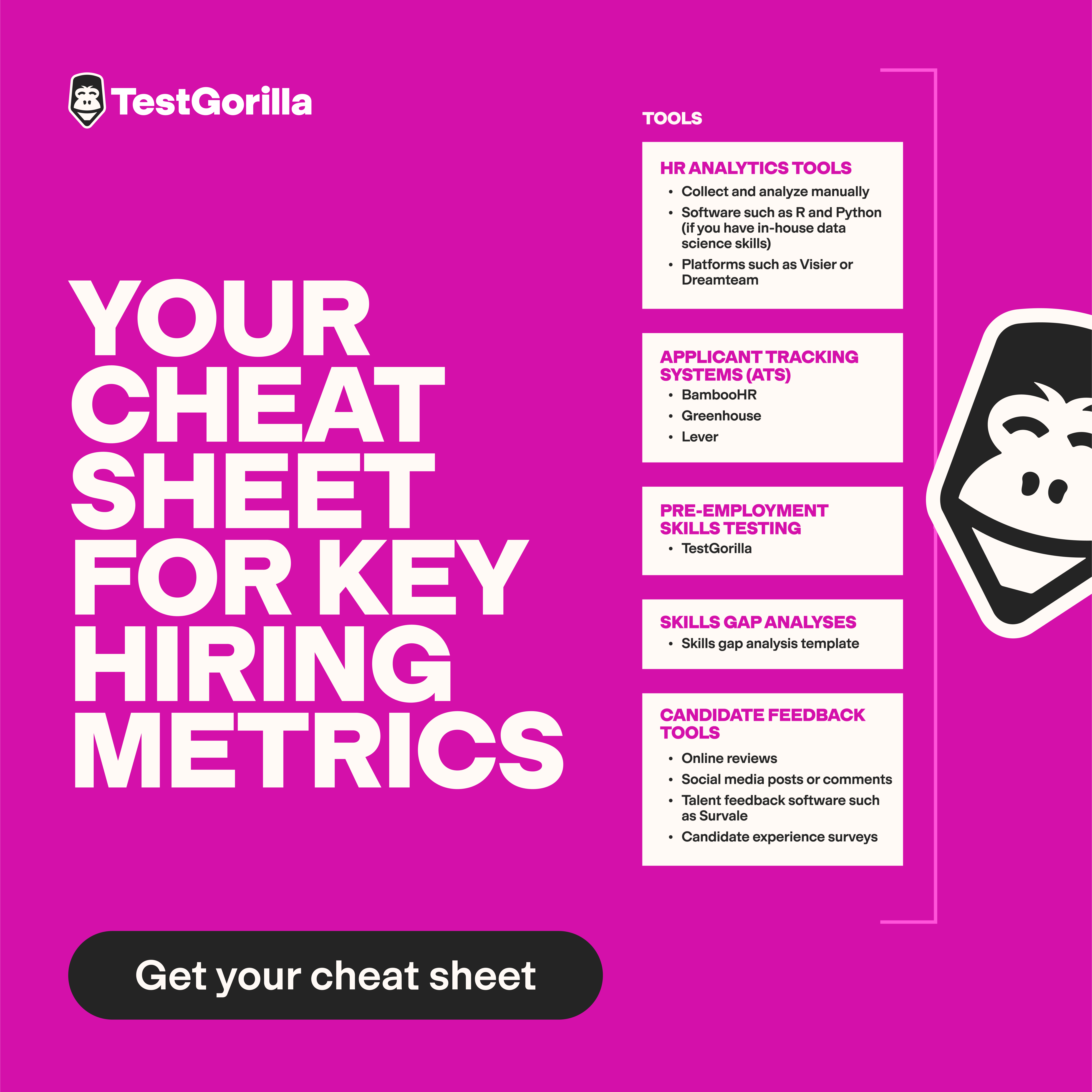

Instead, more and more organizations are turning to skills tests to identify candidates who are qualified regardless of their educational background.

Our own State of Skills Based Hiring 2022 report found that 76% of companies are already reaping the benefits of skills-based hiring, with 89.8% seeing a decrease in cost-to-hire, 91.4% seeing a decrease in time-to-hire, and 92.5% seeing a reduction in mis-hires.

This is part of an overall shift known as the “degree reset.” But what role does skills-based hiring really have in this reset, and where do universities go from here?

In this blog, we discuss the role that universities have played in hiring up until now and how we see that changing in the coming decades.

Table of contents

What role have universities played in traditional hiring?

For hundreds of years, universities were sites of research and innovation for a privileged subsection of society. They had little to do with working people and instead set their sights on broadening our understanding of the world around us.

All this began to shift in the second half of the 20th century.

1960s – 1970s: Preparing for a new era of work

As Baby Boomers started to arrive on campuses in the 1970s, many colleges struggled with the sudden surge in demand.

From teaching staff to dormitory space, colleges were scrambling to find the resources to accommodate all of these new students, many of whom were women looking to gain the skills to work in jobs now open to them.

However, college administrators knew that this wave would end in a couple of decades. The birth rate would normalize again and enrollments would shrink, so colleges would be left in a crisis.[2]

But big changes were brewing in the world of work that would eventually avert this.

1980s – 2000s: Screening candidates for professional skills

In the late 20th century, Western society was experiencing a seismic shift in the world of work as we shifted from an industrial society into what economist Peter Drucker called a “knowledge economy.”

Instead of the economy being driven by physical labor, there was a shift to “knowledge work” brought about by the rise of information processing.[3]

Knowledge work is often defined as work in which employees are required to “think for a living” with their main output being decision-making, analysis, problem-solving, and strategy.

Universities were called on as disseminators of knowledge to provide the skilled workers to take up these roles, essentially saving colleges from the enrollment cliff they had anticipated in the 1970s.

This continued when knowledge work and digital work became even more entrenched throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s.

Degrees became a convenient proxy for the kind of professional skills that were now a baseline for many jobs, such as communication and presentation skills.

With more and more jobs requiring a university education, this further pushed many young people to colleges and universities. The 2008 recession only accelerated this when many unemployed workers turned to education to improve their employee profile.[4]

This led to a phenomenon known as degree inflation, in which degrees were required for jobs that had never previously needed them.

For example, by 2015, 67% of production supervisor roles required a college degree, while only 16% of existing production supervisors had one.[5]

2010s: Unable to stop skills shortages

Despite the fact that universities claimed to give graduates the skills required for “knowledge work,” these skills were not materializing.

By 2019, 87% of companies worldwide reported that they either already had skills gaps in their workforce or expected to experience them within a few years. In the same year, only 27% of small companies and 29% of large companies believed they had the right talent for digital transformation.[6]

It wasn’t only employers that were unhappy.

Many students were frustrated that their programs weren’t preparing them more directly for the world of work. In 2015, a UK study found that 92% of students wanted work experience opportunities to be a part of their university degree, but less than half had access to them.[7]

This lack of business exposure was affecting graduates’ careers. In 2022, almost 40% of recent college grads were underemployed in the United States, and this was after most grads had made a significant financial investment in their studies.

The average federal loan debt in 2023 stands at more than $37,000, but the average total including private loans could be more than $40,000.

By the time the 2020s rolled around, college degrees were looking more like a poor investment for both employers and employees, so as a result, businesses began shifting the focus of their hiring away from degrees and towards skills.

This movement is known as the “degree reset.”

What is the degree reset?

The degree reset is a term coined by the Burning Glass Institute to refer to the de-emphasis of university degrees by employers during the hiring process.

Their report found that 46% of “middle-skill” and 31% of “high-skill” jobs had experienced degree resets between 2017 and 2019.

This movement is driven by two types of factors: structural factors and cyclical factors.

A structural reset

As we’ve seen in the brief history above, the identity crisis that universities are now having has been building for a long time due to structural changes in the workforce and the economy.

Colleges had saved themselves from one enrollment crisis by rebranding as the source of the professional skills needed for a new age of work, but the evident failure to successfully evolve into this role has found them hemorrhaging funding and students.

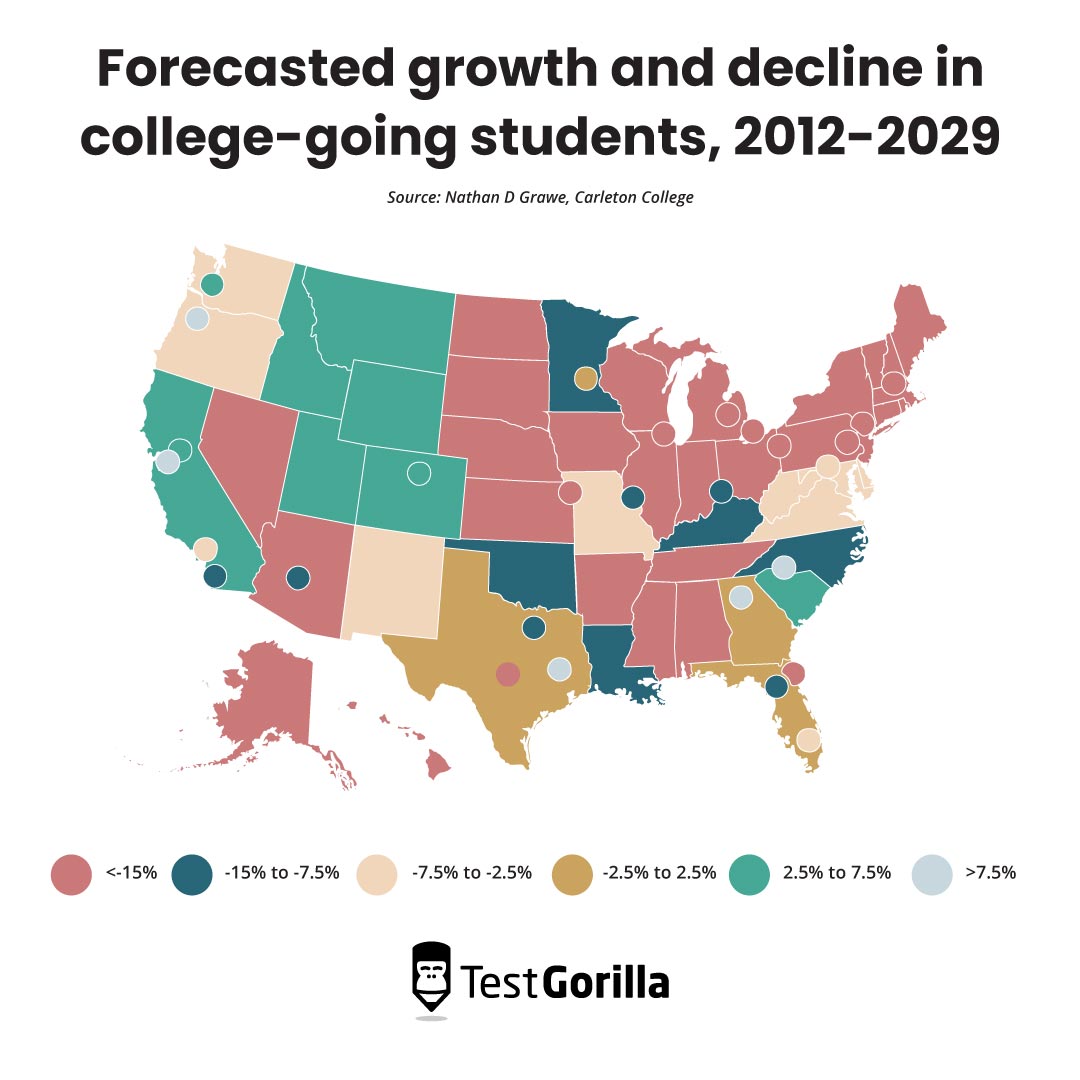

This is shown first in declining enrollment. From 1985 to 2010, college enrollment increased by 2.2% per year on average, but from 2011 onward it began falling at an average rate of 1% per year. [8]

Not only that, but the rate at which students complete their studies has stagnated at around 60% for the class of 2020.

Employers have also increasingly been waking up to the fact that degree requirements cut out huge swathes of the workforce. A massive 60% of American workers over the age of 25 do not hold a four-year degree but may be skilled through alternative routes, such as professional apprenticeships.

Employers are also realizing that disqualifying candidates based on not having a degree disproportionately impacts marginalized communities.

Indeed, including a four-year degree requirement in your screening process automatically cuts out 76% of African Americans and 83% of Hispanic workers due to the fact that many people of color are held back in the education system by systemic bias.[9]

Studies repeatedly show that children of color, particularly those from low-income households, are significantly more likely to be disciplined by educators for behaviors that are tolerated when performed by their White classmates.

Their punishments are also more likely to be severe, such as suspension or expulsion, with some studies suggesting this starts as early as preschool.

This naturally affects ethnic minorities’ educational outcomes and their likelihood of reaching college, therefore making it much harder for employers to hire diverse candidates when using degree requirements to screen candidates.

It’s not only racial diversity that degree requirements affect, either: A four-year degree requirement also screens out 81% of Americans in rural communities, which reduces the ability of recruiters to create a diversity of thought within their companies.[10]

Clearly, the degree reset has been a long time coming and is underpinned by structural factors. However, it has also been accelerated by short-term, “cyclical” factors.

A cyclical reset

So far, we’ve focused on the structural factors driving the degree reset, but the Burning Glass Institute’s report also identified “cyclical” factors influencing it: short-term fluctuations in the labor market and economy that have pushed the concept to the forefront.

The Covid-19 pandemic has naturally been a factor that has accelerated the rate at which the degree reset is taking effect across industries.

This is primarily because it affected college enrollments. The number of students attending college dropped by 2.5% from 2020 to 2021, an acceleration of the steady decline in college enrollment observed over the past decade.

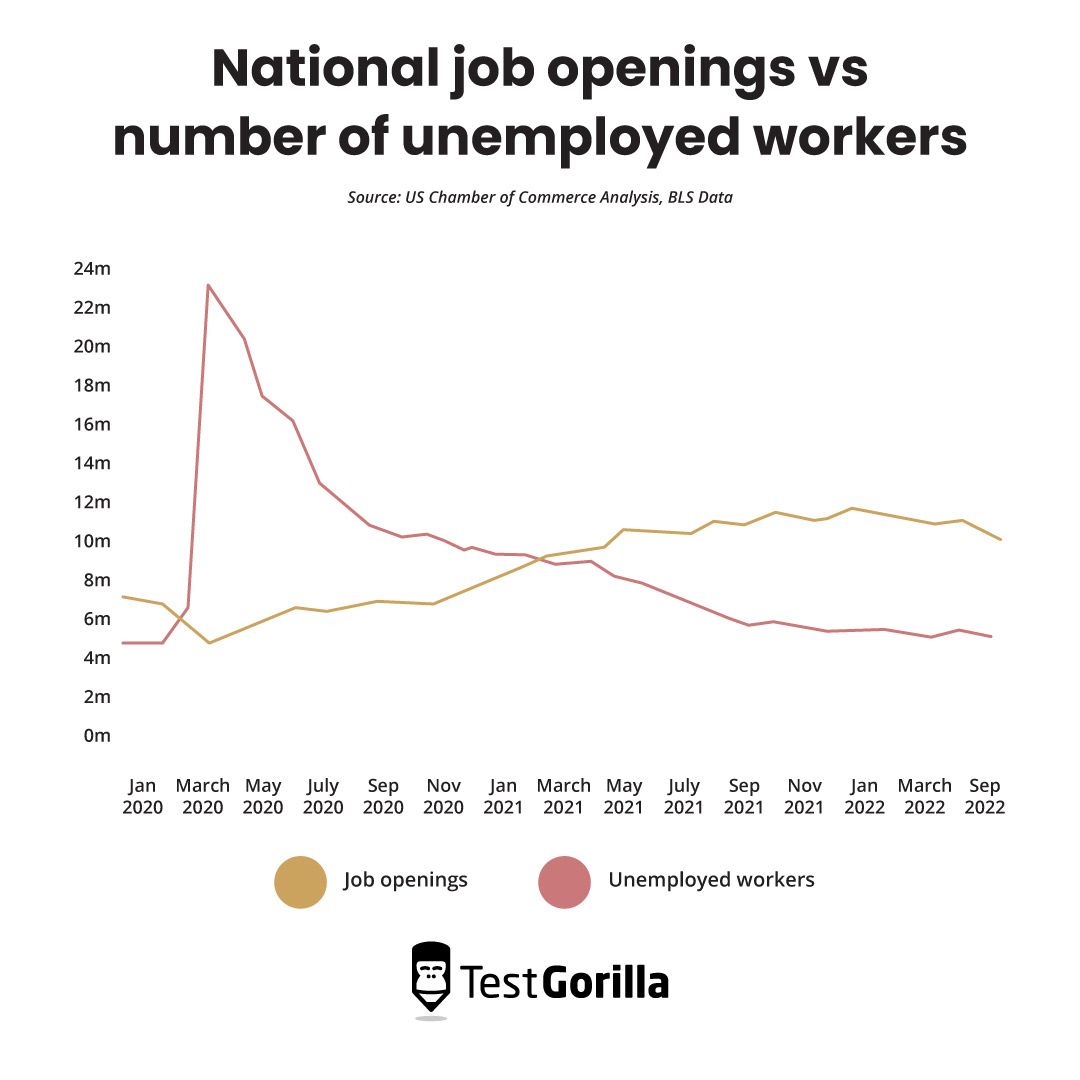

As we all well remember, the pandemic also had a huge effect on the labor market. In fact, unemployment spiked higher in three months of Covid-19 than it did in two years of the Great Recession – an unprecedented upheaval.

Since the beginning of the “new normal” post-lockdown, many experts have declared it a “candidate’s market,” a phenomenon that occurs when the number of open roles exceeds the number of qualified candidates who can fill them. Indeed, 75% of companies in 2022 say they’re facing talent shortages – the highest in 16 years.[11]

In a candidate’s market, employers face tougher competition when filling open positions, and this gives candidates more power when negotiating their contracts.

Removing barriers to applying, like a four-year degree requirement, is a solution that many employers have used to bridge the skills gaps observed across industries to ensure skilled candidates are not needlessly being filtered out.

However, as we can see, this is merely an acceleration of a much longer-term trend. The question now is: What’s the future of college degrees in this skills-driven labor market?

The best insights on HR and recruitment, delivered to your inbox.

Biweekly updates. No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Where do universities go from here?

It’s clear how the shift to a skills focus has driven the degree reset. But where do employers and policymakers go from here? What is the role of the university in this new landscape?

Here are our predictions for how the role of the university will change over the next few years.

Re-centering knowledge

Much of the discussion around the degree reset doesn’t challenge the idea of the university that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s – in other words, its role is to provide students with skills for the job market.

For this reason, when people talk about the future of the university after the degree reset, they often focus on the cyclical factors influencing the reset.

Solutions tend to be short-sighted, focusing on reversing cyclical factors by making a university degree more skills-focused.

One example is the UK government’s now-withdrawn “Restructuring Regime.” This scheme incentivized universities to focus on subjects that deliver graduates into roles with “economic and societal importance,” using examples of STEM, nursing, and teaching.

This regime inevitably led to the shuttering of many humanities programs which are seen to deliver fewer “employable” skills than their STEM counterparts. These include master’s programs in subjects like refugee studies, development studies, and education for sustainability.

This trend is destructive for many reasons.

One is that humanities programs are a key site for skills training – but in “soft skills” rather than “hard skills.” Although soft skills are often perceived to have less value in the labor market, they are becoming increasingly important.

Deloitte research suggests that two-thirds of all jobs in 2030 will be soft-skill-intensive, with the number of jobs available in such occupations set to grow at 2.5 times the rate of those in other occupations.[12]

However, we would argue that this notion that universities have a primary output in skills is mistaken in the first place. This is because universities were sites of knowledge development before they were branded as sites of skill development, but the requirements for obtaining a degree did not change much during this shift.

Therefore, universities remain ill-equipped for providing students with professional skills. Regardless, the knowledge they do provide has many important roles to play in our society, so universities are still invaluable as places of learning.

The thinking that occurs on college campuses is essential to our development both as a society and as individuals. This includes not only scientific discoveries but also boundary-pushing cultural criticism and historical research, for example in the field of gender studies.

Colleges are also an important space for young people to explore their identities and develop socially and politically.

Many era-defining cultural movements start on college campuses. These include the Berkeley free speech movement in the 1960s and the “Carry That Weight” protest against sexual assault at Columbia University in the 2010s.[13] [14]

The thinking that fuels these movements is often inspired by non-vocational teaching in programs like art, history, and politics. None of these can be directly replaced by “skills-based” learning, but all of these courses nonetheless impart skills that create innovative professionals, including creativity and critical analysis.

Knowledge also offers a necessary context for skills, such as in disciplines like economics. Employers might urge educators to focus on imparting hard skills to economics students, which include data collection, analysis, and interpretation. However, these skills require a strong understanding of economic theories and the history of economics in order to become useful in the workplace.

Finally, although students undoubtedly develop employable skills while studying these disciplines, it is unreasonable to expect that every student arriving at college at eighteen knows what career they want and therefore what skills to target.

Clearly, looking to colleges to churn out well-rounded professionals as their primary function was always a doomed endeavor.

The institution isn’t broken, necessarily – colleges as knowledge-based institutions provide value to our society – but this single-minded expectation is.

We need to “deprogram” our notion that universities primarily exist to provide employable skills and open the field for skills provision to other avenues.

Broadening options for skills development

Solutions like the one proposed above – for universities to put their energy into more “employable” disciplines – are focused on preserving universities’ status as the engines of skill development in our economy.

However, this goes against the structural influences of the degree reset, which show a long-term shift toward recognizing that employable skills can and should come from anywhere.

This means opening employers’ minds to candidates from different skills backgrounds, which might include:

Community college

Workforce training

Certification programs

Military service

On-the-job training

Self-guided training

In the short term, we expect that policies like the one discussed above will encourage many colleges to be more explicit about the hard and soft skills that students learn on all programs.

For instance, colleges might explicitly include skills testing in degree evaluation or start offering “professional skills” modules to all undergraduates.

We can also expect to see universities offering more programs that are focused primarily on skills-building as well as offering short, skills-based programs as precursors to bachelor’s degrees or supplemental learning after graduation, especially online.

For instance, Shippensburg University is already offering short-term skill-building programs in topics like supply chain management.

Other colleges are starting to offer modules in partnership with industry leaders, often as a core requirement for a related degree. Rochester Institute of Technology offers “cooperative education” in partnership with businesses, as well as arranging internship opportunities for students in STEM subjects.

We hope that the long-term shift away from a degree focus in hiring means that we will see more focus on skill development outside of universities, too.

Employers might consider utilizing apprenticeship programs in addition to upskilling and reskilling initiatives to develop young workers through the workforce.

It’s already happening in some organizations: Achieve Partners have created a $180m fund to invest in businesses that are providing apprenticeship programs in sectors plagued with skills gaps, including IT and healthcare.[14]

You might consider leading the charge in your own organization by applying skills-based hiring techniques to develop the skills in your workforce. You can use skills testing to:

Identify skills gaps in the workforce

Notice gaps in individual employees’ skill sets

Track skill development as upskilling progresses

Many companies across industries are already embracing upskilling tactics as a means of improving their employer brand and standing out to top candidates.

It’s a prudent move; one Gallup study found that 65% of workers believe employer-provided upskilling is very important when evaluating a potential new job. This could certainly help you navigate the challenges of the current candidate’s market.

Expecting reduced enrollment but higher completion rates

With the above trends in mind, we can expect that university enrollment will continue to decline over the next few years. Some experts suggest it may even fall by as much as 15% after 2025.[15]

While most institutions will survive, it is possible that many institutions will be forced to shutter their programs as the over-inflation of degrees reduces, with the most at risk likely to be less well-known institutions and regional colleges.

Diversity is also likely to drop in traditional humanities programs as cheaper options are closed down unless these universities intentionally push to promote these disciplines.

Other colleges, however, may combine strategies, streamlining their program offerings while also applying the more skills-based approach we’ve already discussed.

An early example is the University of Tulsa.

The college is phasing out 84 of its low-demand degree programs and grouping its business, health, and law colleges into one professional school, with the overall teaching structure shifting away from traditional academic departments towards interdisciplinary divisions.[16]

With a broader array of course options on offer and less pressure for students to take on college at any cost, it’s likely that the stagnation in completion rates we observed in the late 2010s could improve.

Increasing accessibility to combat falling enrollment

We can’t expect universities not to put up a fight against falling enrollment.

Tuition costs have been increasing drastically for decades because colleges have taken advantage of the demand for degrees and invested in resources required for maintaining high enrollment. Tuition and fees in the United States have jumped massively, by:

134% at private national universities

141% for out-of-state tuition and fees at public national universities

175% for in-state tuition and fees at public national universities

This could all change in the coming years.

First, the trend for online learning was accelerated by the pandemic and is now becoming part of more universities’ long-term course offerings. Online learning is frequently cheaper for colleges to run and for students to access, so this could help protect colleges against a sharp drop in enrollment.

As demand for in-person programs continues to decline, it’s possible that university degrees will become more accessible financially to encourage more students to enroll.

President Biden’s debt relief plan, which includes an income-driven model for debt repayment, may also make students more likely to enroll by lessening the debt burden of college.

This would continue the trend that has been emerging over the past few years of private colleges offering tuition discounts as a means to boost enrollment

This could potentially slow the transformation of the university that we’ve outlined above: from a knowledge-based institution credited as a skills provider to a hybrid institution that’s a respected option for professional skills development.

Step into the future of skill development by embracing skills-based hiring and learning

For employers, the degree reset is an opportunity to broaden your horizons when it comes to candidate selection, opening your applications to STARs and hiring candidates for their skill sets rather than the content of their resume.

But hiring is only the beginning. You also need to develop your employees’ skills continuously to remain competitive.

To find out how to do this, read our blog about how to apply skills-based learning in your organization.

To discover the other changes the switch to a skills-based approach is bringing, check out our article on how a skills focus revolutionizes your approach to retention and internal mobility.

Or if you’re ready, use our skills tests to directly measure the skills you’ve previously used degree requirements as a proxy for, like mechanical reasoning and reading comprehension.

Sources

Fuller, Joseph; Raman, Manjari. (October 2017). “Dismissed by Degrees”. Harvard Business School. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/dismissed-by-degrees\_707b3f0e-a772-40b7-8f77-aed4a16016cc.pdf

Carey, Kevin. (November 21, 2022). “The incredible shrinking future of college”. Vox. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/23428166/college-enrollment-population-education-crash

Drucker, Peter F. (September-October 1992). “The New Society of Organizations”. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://hbr.org/1992/09/the-new-society-of-organizations

Parker, Clifton B. (March 6, 2015). “The Great Recession spurred student interest in higher education, Stanford expert says”. Stanford News. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://news.stanford.edu/2015/03/06/higher-ed-hoxby-030615/

Fuller, Joseph; Raman, Manjari. (October 2017). “Dismissed by Degrees”. Harvard Business School. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/dismissed-by-degrees\_707b3f0e-a772-40b7-8f77-aed4a16016cc.pdf

Snyder, Scott. (January 11, 2019). “Talent, not technology, is the key to success in a digital future”. World Economic Forum. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/talent-not-technology-is-the-key-to-success-in-a-digital-future/

“Student Employability Index 2015”. (January 28, 2015). National Centre for Universities and Business. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://www.ncub.co.uk/insight/student-employability-index-2015/

Welding, L. (2023, May 2). U.S. college enrollment decline: BestColleges Data Center. Find the Best Online College or University for You! | BestColleges . U.S. College Enrollment Decline | BestColleges Data Center

“Highest Educational Levels Reached by Adults in the U.S. Since 1940”. (March 30, 2017). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/cb17-51.html

Marré, Alexander. “Rural Education at a Glance, 2017 Edition”. (2017). US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Retrieved March 02, 2023. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=83077

“The Talent Shortage”. (2023). ManPowerGroup. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://go.manpowergroup.com/talent-shortage

O’Mahony, John; Rumbens, David. (May 2017). “Soft skills for business success”. Deloitte Access Economics. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/economics/articles/soft-skills-business-success.html

Gambino, Lauren. (May 19, 2015). “Columbia University student carries rape protest mattress to graduation”. The Guardian. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/may/19/columbia-university-emma-sulkowicz-mattress-graduation

“Education Investors’ Latest Fund Will Deploy $180M to Building Apprenticeships in High-Demand Fields”. (June 29, 2021). PR Newswire. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/education-investors-latest-fund-will-deploy-180m-to-building-apprenticeships-in-high-demand-fields-301321923.html

Barshay, Jill. (September 10, 2018). “College students predicted to fall by more than 15% after the year 2025”. The Hechinger Report. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://hechingerreport.org/college-students-predicted-to-fall-by-more-than-15-after-the-year-2025/

Nietzel, Michael T. (April 18, 2019). “Planning The Future Rather Than Waiting For It: The University Of Tulsa’s Reimagining”. Forbes. Retrieved March 31, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaeltnietzel/2019/04/18/planning-the-future-rather-than-waiting-for-it-the-university-of-tulsas-reimagining

You've scrolled this far

Why not try TestGorilla for free, and see what happens when you put skills first.