How the “low-skill” label is hurting the workforce (and how to fix it)

The Coronavirus pandemic turned the world of work upside down, and not just for office workers who had to work out how to conduct meetings over Zoom. It also spelled huge changes for so-called “low-skilled” workers.

Almost overnight, they went from being the butt of the joke (“If all else fails, I’ll just end up flipping burgers”) to frontline heroes as we recognized just how heavily we rely on their labor for our society to run smoothly.

Grocery cashiers, delivery drivers, hospital porters – they all received new recognition and were even inducted into the U.S. Department of Labor’s Hall of Honor in 2022.[1]

And yet, when we look at where we are on the slow climb out of the pandemic, what has really changed? Restrictions have been lifted, but so-called “low-skilled” work is still frequently the lowest-paid.

Can it be true that “low-skill” jobs are essential in times of emergency and yet require no skill to perform? Or do employers need to adjust their perspective on these roles and recognize the vast range of valuable skills they encapsulate?

We’re on the latter side, and in this blog, we talk you through the myth of “low-skilled” work and how employers can eliminate that outdated descriptor from their vocabulary.

What do we mean by “low-skill” jobs?

First, it’s important to talk about what “low-skill” work has meant historically. “Unskilled” or “low-skill” are antiquated terms often applied to workers who are seen to have less power in the labor market. This is usually because they lack a high school diploma or college degree or because they have lower digital literacy skills.

“Low-skill” jobs are roles that don’t require prior training or extensive experience to perform and don’t require complex machinery or computing knowledge to complete. Examples include cashiers, wait staff, cleaners, and many other service industry professionals.However, an increasing number of people[2] in the U.S. don’t have a high school diploma, and nearly one-third of US workers lack digital skills. By the above definition of “low-skill” work, this large group of individuals has little to offer employers, but we argue that this assessment is false.

Designating “low-skill” jobs negates valuable skills

To look at the above list of jobs and see only “low-skill” roles is to take a very selective view of what is required in each profession. Take the role of a cashier. To perform this job well, you need many tangible skills, for instance:

Basic math skills to check balances are correct

Attention to detail to pinpoint issues with transactions and recall offers and protocols

Problem-solving skills

That’s not to mention the soft skills required in these kinds of roles, including communication skills for dealing with customers, emotional regulation, and the right personality for customer-facing work.

These kinds of skills are not to be dismissed. In our own State of Skills-Based Hiring Report for 2022, over 73% of respondents believed that it is more important now for candidates to have great soft skills than it was five years ago.

The skills required in so-called “low-skill” jobs are also transferable to other roles. For example, many of the same skills required in customer-facing roles like a cashier are also employed in “middle-skill” positions which require some training after high school but not a college degree. An example might be a paralegal role, which also requires:

Discipline and the ability to abide by company behavioral guidelines

Clear communication when interacting with clients and colleagues

Empathy concerning clients’ difficulties

Conflict resolution when dealing with disagreements among team members and customers

These skills are transferable to management to leadership roles as well. From this perspective, we see that these roles are not low-skilled. So, what are we talking about when we refer to these roles this way? In many cases, we believe that we use “low-skilled” to simply mean “low-wage.”

The best insights on HR and recruitment, delivered to your inbox.

Biweekly updates. No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Does “low-skill” just mean low-wage?

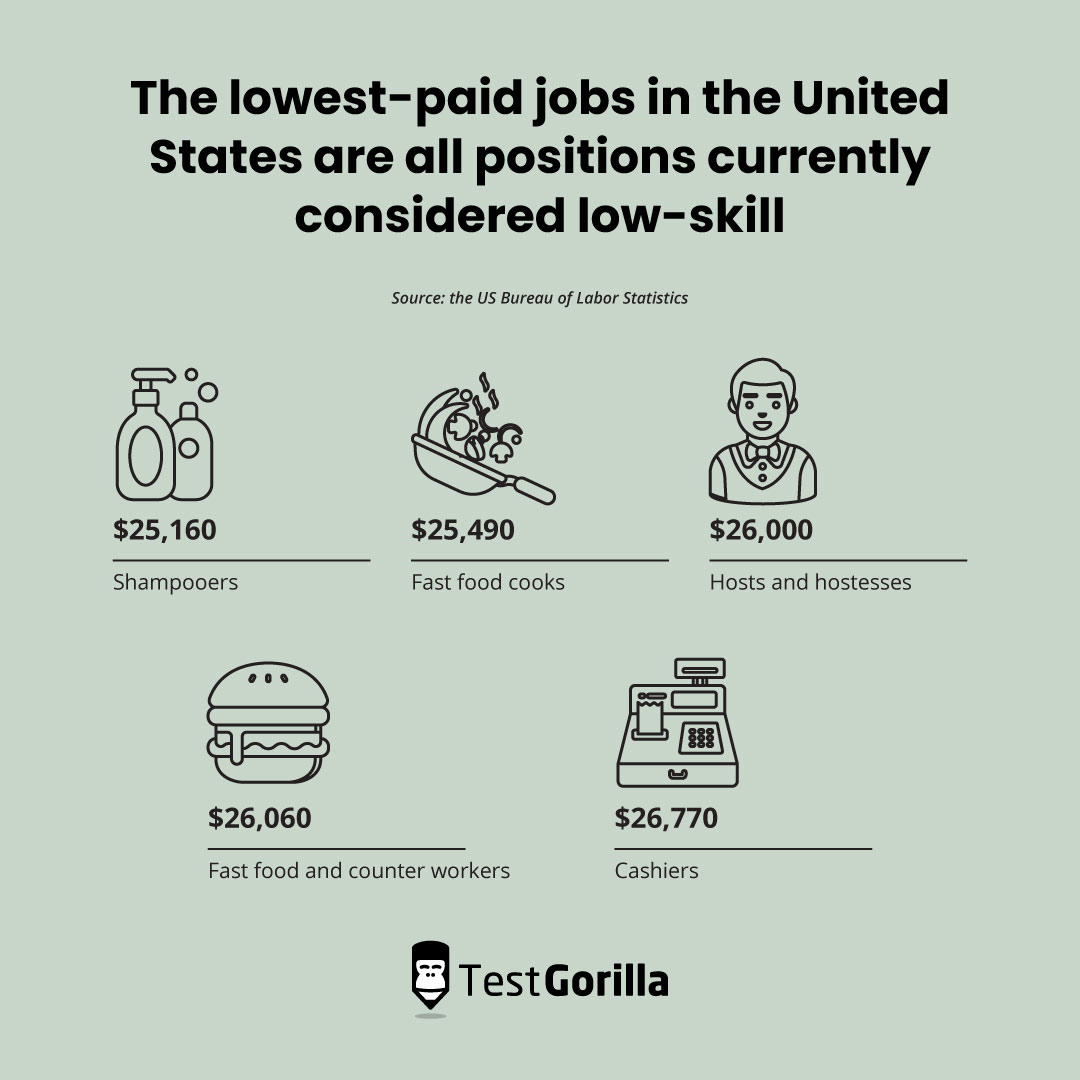

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the lowest-paid jobs in the United States are all positions currently considered low-skill. They include:

Shampooers ($25,160 per year)

Fast food cooks ($25,490)

Hosts and hostesses ($26,000)

Fast food and counter workers ($26,060)

Cashiers ($26,770)

To understand why these roles are so poorly-compensated despite requiring the skills we discussed above, let’s look at the highest-paid professions for a contrast. According to the same dataset, the highest-paid profession in the U.S. is cardiology, where professionals earn, on average, $353,970 per year.

Even in an ideal world, it’s likely that cardiologists would be paid more than cashiers. It’s a role that requires years of medical training, both in higher education institutions and on the ground at hospitals. It incurs a lot of responsibility, and nobody would argue that this is not a highly-skilled job.

But just because cardiology is a highly-skilled profession does not mean that the mechanisms in place for cardiologists to gain their skills are the only ones through which any useful skills are gained, nor that highly-specialized skills are the only worthwhile kind.

It’s also true that skill is not the only factor in cardiologists’ high pay. The amount of potential revenue that a role can generate for an organization is an equally powerful influence. In addition to being complex and risky, cardiology procedures are some of the most profitable for hospitals in the U.S.

Meanwhile, in the U.K., which has a nationalized healthcare service, cardiologists’ pay is considerably lower, at an average of £93,764 or US$116,584. This is still a competitive salary but much lower than the U.S. figure.

With this in mind, it may therefore be that the decisive difference in the gap between high-, medium-, and low-skill positions is not purely the amount of training that candidates bring with them into the workforce but how much visible influence they have over an organization’s bottom line.

At first, this might not seem like a problem that employers need to solve. Some leaders might argue that a cashier doesn’t contribute in an obvious way to a business’s profits, and they should be paid less for their work. However, we believe there are several big reasons why this isn’t the case.

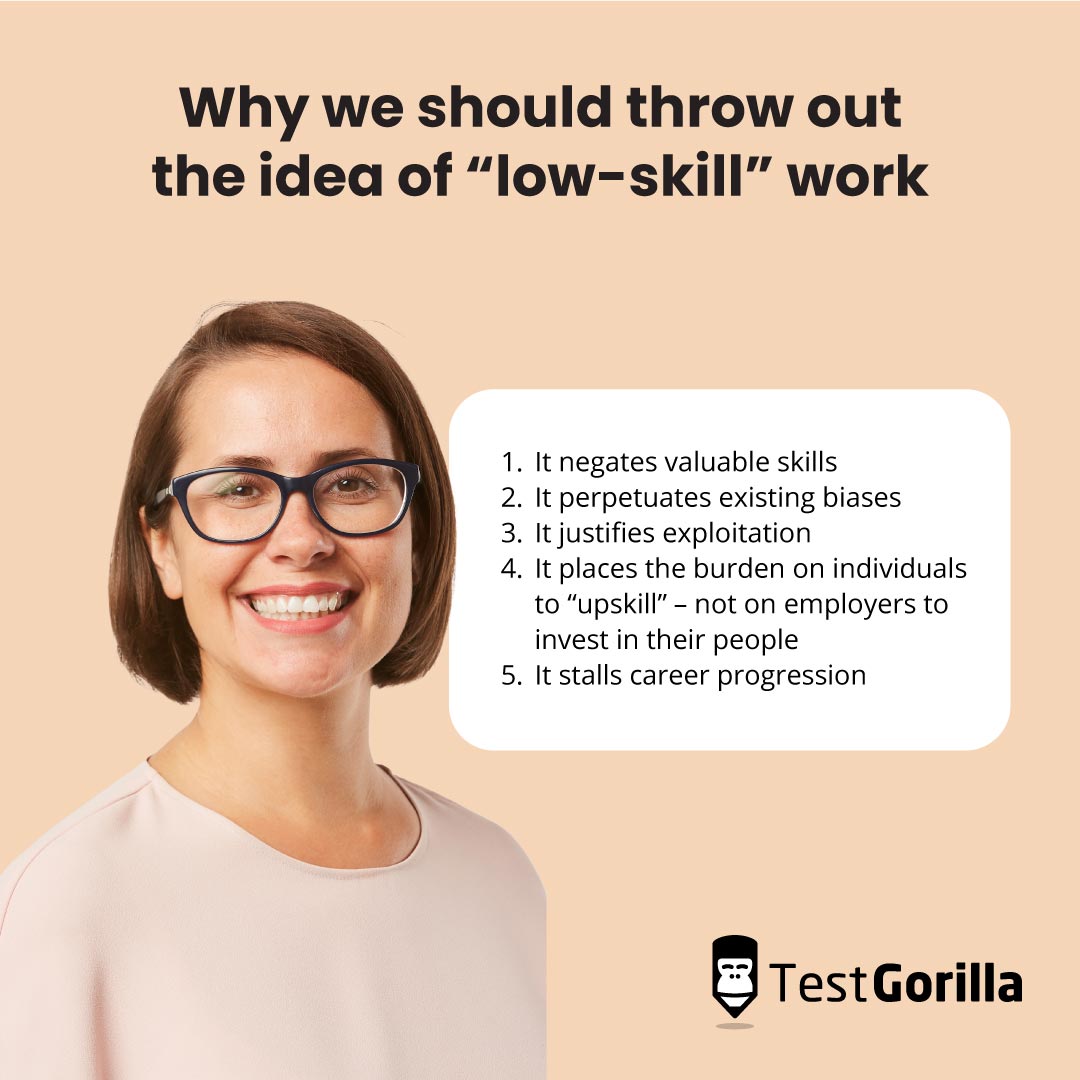

Why we should throw out the idea of “low-skill” work

It’s not just that the label “low-skill” is inaccurate; it’s actively harmful, meaning businesses should scrap it altogether – here’s why.

1. It perpetuates existing biases

As we mentioned above, the definition of “low-skill” and “high-skill” roles is highly dependent on formal education, particularly the completion of at least one university degree.

This is a biased position that employers often take when hiring. Instead of testing applicants to see what they can actually do, they use a college degree as a substitute for a whole range of skills that may not even be taught as part of that candidate’s major, like digital literacy skills, for instance.

This is especially common in “middle-skill” jobs affected by automation and contributes to the phenomenon known as “degree inflation.” This refers to degrees being required for roles that previously didn’t ask for them and (probably) don’t really need them.

This isn’t just meaningless jargon. Degree inflation has had a tangible effect on employment trends. Compared to 2010, employment rates among 25- to 34-year-olds were higher in 2021 – but only for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Not only is requiring a degree as a shorthand for digital skills an ineffective way to hire, but it also props up other biases due to the educational inequality within the United States.

Recent research has found that the existing achievement gaps between white students and students of color in the U.S. widened during the pandemic.). These inequalities are reflected in the types of skills that different demographics are likely to have.

To give just one example, more than half of Latino workers have limited or no digital skills and a quarter of them only have access to the internet via a smartphone. Latino people make up almost one-fifth of the U.S. labor market and will account for half of all new workers by 2025 – that’s a big chunk to exclude.

By insisting on college degrees as a shorthand for “employable skills” and consigning all other workers to “low-skill” (i.e., low-wage) jobs, you’re disadvantaging already underrepresented minorities and missing out on a large section of the candidate pool and myriad opportunities for innovation.

The benefits of diversity for business are well-known, but these efforts have long-neglected low-wage workers. Extending these efforts into low-wage positions could have potentially transformational effects for your organization.

2. It justifies exploitation

By being selective about which skills we value in the workplace, we justify reducing support for “low-skill” workers. This means driving down wages so that they don’t cover living costs and eliminating access to benefits – or even forcing “low-skill” employees to work in poor conditions, prioritizing efficiency over worker safety or wellbeing.

We can see an example in the recent allegations from factory workers at Amazon, who have accused their employer of exploitative practices, such as inadequate safety procedures to prevent COVID infection in warehouses.

This risk is especially pertinent to “low-skill” jobs because the low barrier for entry in terms of prior qualifications makes these popular roles for already vulnerable populations, such as immigrants and refugees.

You might think that you’re exempt from this pattern of exploitation because you treat all of your employees with respect – but does that include roles that you’ve outsourced either domestically or internationally?

It’s no secret that outsourcing to countries where labor is especially cheap can often promote the exploitation of workers, but domestic outsourcing has its issues too.

In particular, it removes the burden of caring for your low-skill workers from your organization, passing it instead to other companies whose business practices you can’t influence and which may not align with your outward values.

Consider janitorial work. A few decades ago, your company or office building might have had a dedicated janitorial staff to take care of it. Now, most offices use outsourced cleaning services. Some research even suggests that outsourcing janitorial and security services leads to wage penalties for low-wage service occupations.

Driving down wages is not the only negative impact these practices have on “low-skill” workers, either.

3. It places the burden on individuals to “upskill” – not on employers to invest in their people

Upskilling your workforce should be a top priority for any forward-thinking organization. It helps you address skills gaps in your workforce, makes you a more attractive employer, and is even recommended to help promote innovation.

However, “low-skill” workers are often left out of these initiatives. The very title suggests that they offer the bare minimum to the workforce.

Unlike those in “middle-” or “high-” skill professions, “low-skill” workers are not seen to be pursuing careers or developing a set of skills they can then use to progress upwards in the workforce. They are simply there to fulfill a basic function of the business.

This means that if an employee wants to break out of this cycle, the expectation is that they do it themselves instead of seeking support from their employer. They might do this by attending night classes outside work. However, even this may not be a viable path to progression due to the degree inflation we mentioned earlier.

With degree requirements presenting a barrier to moving into “middle-skill” roles, “low-skill” employees are left with very few options for advancement. This all leads to one conclusion for employees:

4. It stalls career progression

When workers are designated or dismissed as being “low-skill,” internal mobility becomes virtually impossible, at least within the support systems offered by most organizations.

When valuable skills like clear communication are discounted as not being of “real” value to businesses, experience in “low-skill” jobs is seen as a negative rather than a positive – simply because the employee appears to be repeating the same function rather than developing or improving a valuable set of skills.

This is compounded by the lack of investment in so-called “low-skilled” workers from employers, meaning that there are few pathways to advancement within businesses for low-skill employees, for instance, into corporate or management roles.

It is also especially true where outsourcing is concerned. Working in satellite teams siloed away from employees whose offices they clean and the managers who hire them, “low-skill” employees are disconnected from advancement inside and outside their corporate structure.

It’s not a totally bleak picture. There is some evidence that the damage done by calling certain jobs “low-skilled” is felt less in some sectors than others: namely, sectors in which competency in “low-skilled” positions allows those in “high-skilled” positions to better succeed at their jobs.

Examples include a medical or school secretary or an air transport operative, who often see higher wages and better wage progression compared to low-educated workers in industries where soft skills are less valued, such as cleaners or bar staff.

(Interestingly, this trend is especially true in innovative firms and ones that invest more in training their employees – food for thought.)

However, by and large, dismissing the skills required for “low-wage” jobs has tangible costs for individuals and hidden ones for businesses. So, how can you start changing the way you hire to avoid these pitfalls?

How employers can bust the “low-skill” mentality

Now that you know why stratifying roles into low-, middle-, and high-skill categories is damaging to your workforce, here are some ways to actively stamp out this mentality in your business.

The first method is to throw out the degree requirements that prop up this broken system and adopt a skills-based hiring approach instead.

With skills-based hiring, you test candidates on what they can actually do, not just what their school or college transcripts say they were taught. This means that not only can you identify what skills candidates really have, but you can compare their competency in each of these areas more easily.

It’s not only hard skills that you can test, either. You can also test softer skills like communication.

Once you’ve properly adopted skills testing, you can use it to create a skills map of your workforce – not just your managers and office workers, but your “low-skill” staff, too. Talent mapping gives you a comprehensive overview of the skills present in your business, helping you identify opportunities for collaboration and promotion.

As we mentioned earlier, many skills that employees use on the frontline of businesses apply to other corporate structure functions. Pulling an employee with strong institutional knowledge and direct experience with supply chain processes into one of your managerial teams could help drive innovation in your company.

Finally, and perhaps most radically, you can adopt a servant leadership style – in other words, asking not what your employees can do for you but what you can do for them.

This is most relevant to businesses with a large base of frontline workers, like the service industry. A famous example of a servant leader is Cheryl Bachelder, the chief executive officer who took over the failing Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen in 2007.

When she took over, Bachelder realized that senior management within the corporate structure didn’t view their employees as a resource to be maximized but as a nuisance to be silenced.

To combat this, she implemented a servant leadership model, giving franchise owners and teams clear strategic goals, asking them what resources were needed to meet them, and providing those resources.

The results spoke for themselves. Popeyes may have been failing when Bachelder joined in 2007, but when she sold the company to Burger King 10 years later, it fetched almost $2 billion.

There’s no such thing as a low-skill worker

In the past, when we had only crude instruments to help us make hiring decisions, there was more use for stratifying workers into low-, middle-, and high-skilled professions.

However, with the tools at our disposal today, there is no excuse for this outdated thinking. Skills-based hiring tools help us not only to recognize the huge diversity of skills present in our workforce and develop balanced teams but to drive innovation, too.

To get started with skills-based hiring – and banish outdated notions about which workers are worth your effort to recruit – consult our guide on adopting skills-based hiring practices in your organization.

Sources

“Us Department Of Labor Inducts Essential Workers Of The Coronavirus Pandemic Into Labor Hall Of Honor”. (September 1, 2022). US Department of Labor. Retrieved January 12, 2023. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osec/osec20220901

“An Increasing Number of Americans Lack a High School Diploma”. (2011). Clasp. Retrieved January 12, 2023. https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/documents/GED-Landscape-2-5-23-13.pdf

You've scrolled this far

Why not try TestGorilla for free, and see what happens when you put skills first.