Skills-based hiring, impostor syndrome, and the Dunning-Kruger effect

Two candidates sit side-by-side, waiting for a job interview.

One is confident they’ll get the job. In fact, they’re certain of it. They believe they’ve got unmatched skills, exceptional problem-solving, and the makings to be an asset to any organization – despite their lackluster performance in past roles.

The other is less certain of their skills. They secretly suspect that the glowing feedback they get from their colleagues is evidence that they’ve accidentally conned everyone they know or that their past success was a fluke, and they’re afraid the interviewer will suss them out.

This odd couple provides perfect examples of two effects we see a lot in hiring: the Dunning-Kruger effect and impostor syndrome. Unfortunately, we all know which of these candidates will come across best in an interview.

Employers frequently make hiring decisions based on candidates’ self-assurance and perceived personality type, but as the above example shows, using confidence as a guide to skills can lead to ultimately disappointing hires.

Companies can avoid such costly mistakes by encouraging hiring managers to make data-driven hiring decisions: Hire for proven skills, not just confidence. You can do this by adopting a skills-based hiring approach. In this blog, we’ll show you where to start.

The problem with relying on self-reporting to assess skills

Traditionally, recruiters are reliant on candidates themselves to communicate their strengths and skill levels in given areas.

However, there are problems with this approach. First, interviewer bias plays a big part in how traits like confidence are interpreted. Studies have shown that women need to appear “warm” in order for their self-confidence to be well-received, while men are able to express their self-confidence in ways that feel natural to them.[1]

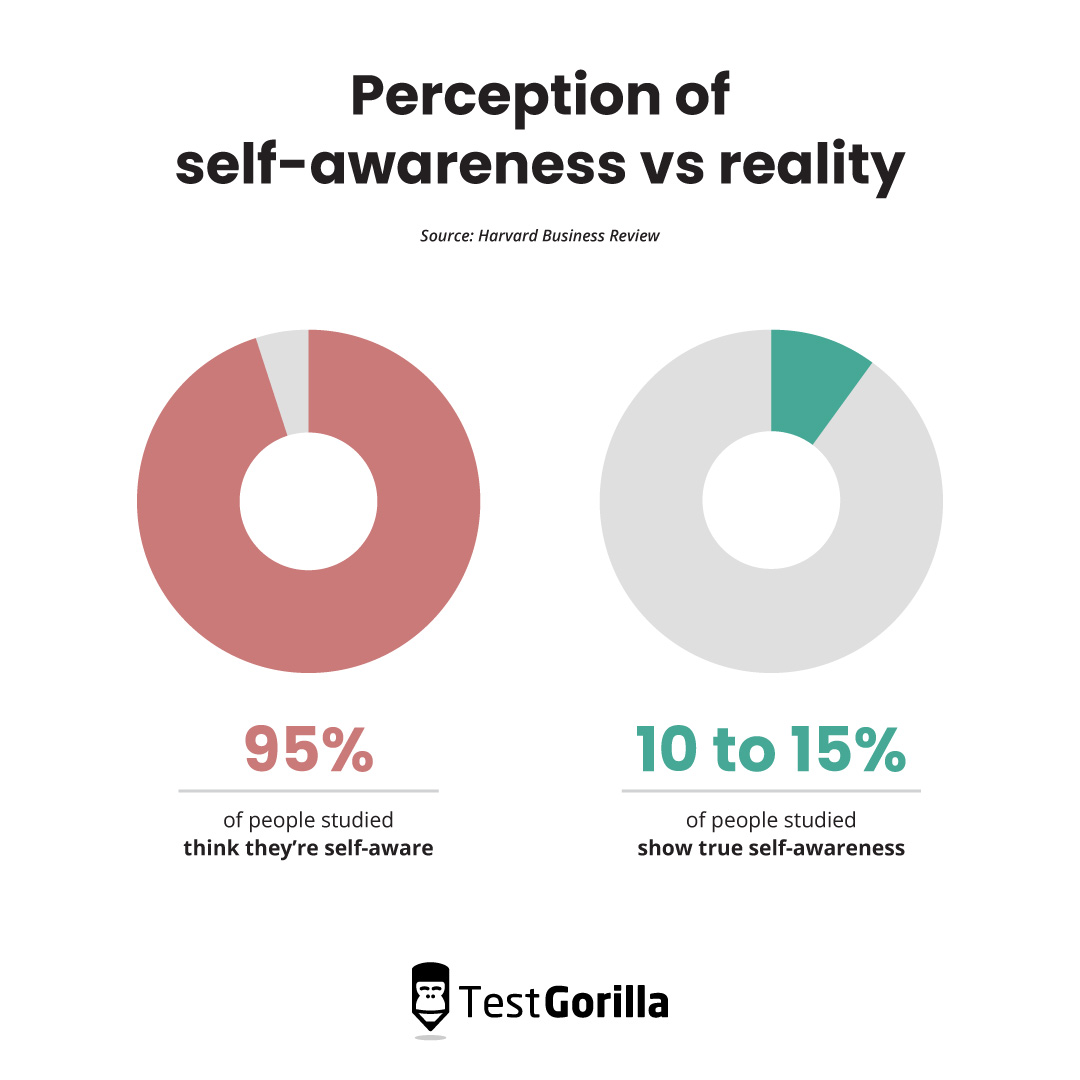

Even if an interviewer took every candidate’s confidence equally seriously, a Harvard study famously found that although 95% of people think they’re self-aware, only 10 to 15% actually demonstrate the traits of true self-awareness.[2] In the course of their study, the researchers discovered two types of self-awareness:

Internal self-awareness: How clearly someone understands their own values, passions, and reactions to situations

External self-awareness: How clearly someone understands the ways other people view them.

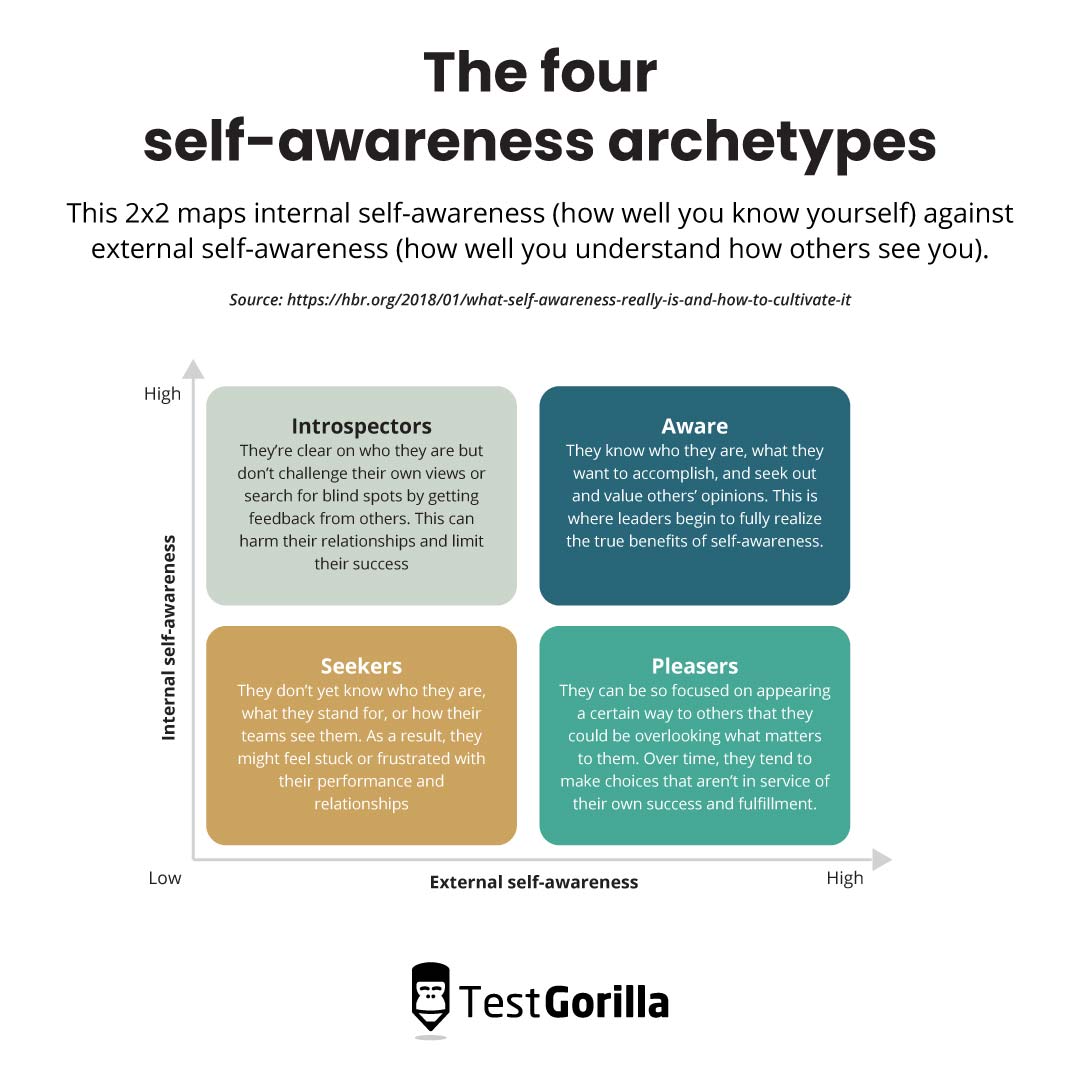

People can possess or lack these types of self-awareness in any combination, creating four self-awareness “archetypes”:

There was virtually no relationship between these two types of awareness – even if someone scored highly in one, that had little bearing on how high the other would be.

True self-insight is rare. In traditional hiring, it’s down to the individual judgment of the hiring manager to determine whether or not a candidate has that insight, and they’re given very little external support to make their decision.

Hiring managers need more data. But where can they get it?

Skills-based hiring is the answer

Skills-based hiring helps mitigate these risks associated with self-evaluation in the hiring process.

You might think we’re being unfair to traditional methods, that the interviewer isn’t entirely unsupported in traditional hiring. After all, they have the candidate’s resume, references, and experience as reference points for their skills. But, let’s think about those for a moment.

To begin, a candidate’s resume is nothing more than a list of their skills with no built-in way to verify them.

Degree requirements are even worse than resumes because you have to simply assume the degree denotes skill. In most cases, degree requirements increase inequality in the workplace by excluding people of diverse backgrounds from employment in middle-skill roles.

Even for more technical degrees, it’s not safe to assume that college graduates have the skills you need. A 2021 survey by SlashData found that JavaScript was the most well-known coding language among developers, but only 42% of student developers in 2018 said they knew JavaScript.[3]

References can be faked if you don’t do your homework. For example, one recruiter only discovered that an employee’s reference was really her boyfriend after the employee had already been hired. Yep, it’s our worst nightmare, too. The amount of people that have friends or family down as fake references is shocking.

Years of experience is also a flawed metric. A candidate’s tenure at a company doesn’t actually tell you how strong their skills are or demonstrate other important qualities, such as leadership and growth, during that time.

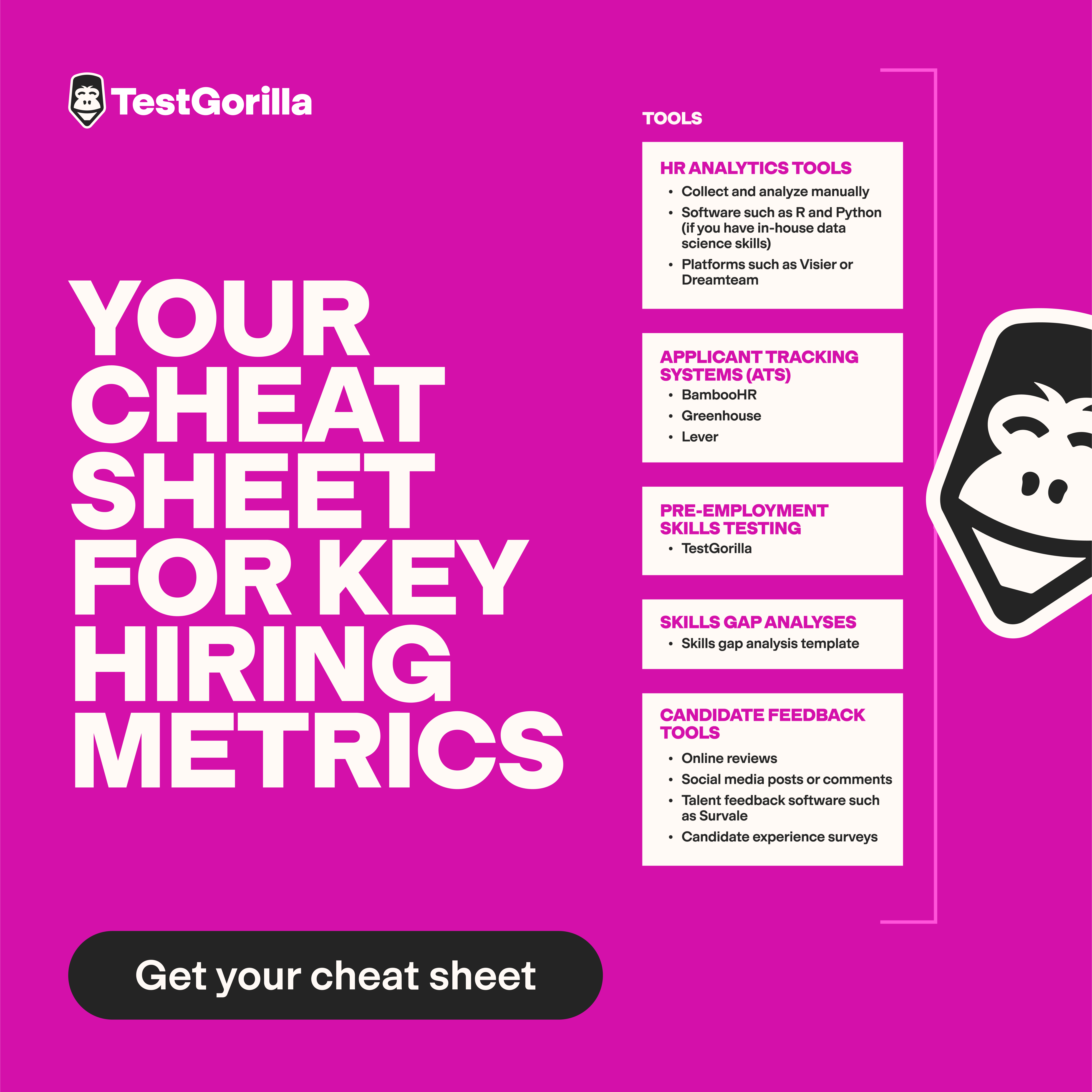

Skills-based hiring allows you to throw out these faulty tools in favor of more precise instruments such as pre-employment skills assessments and structured interviewing techniques.

Of course, you can’t get rid of self-reporting from the application process entirely. Both skills tests and structured interviews still require candidates to tell you about themselves, and you might worry that candidates will only select answers they think employers want to hear when taking personality tests.

However, there are far more safeguards in place against a lack of self-awareness and deliberate manipulation in skills-based hiring.

Our tests use a variety of question types and even work samples, so instead of just telling you about their skills, candidates have the opportunity to concretely demonstrate them.

One of the key question types we use is situational judgment, which presents the candidate with a scenario and asks them to theorize how they would react. Their answers can later be followed up with interviews and reference checks.

There are also things you can do yourself to combat cheating, such as explaining to candidates that you’re not looking for a specific personality type but simply trying to understand who they are.

All of this helps to reduce bias and increase workplace diversity: In our State of Skills-Based Hiring 2022 report, we found that 91.1% of businesses saw an improvement in workplace diversity after using skills-based hiring methods.

Clearly, traditional hiring lets both the candidate’s and the interviewer’s biases get in the way of fair assessment. Biases aside, candidates can also have blind spots about themselves.

Next, let’s explore how skill-based testing can be used to identify and combat any insecurities toward their own abilities.

Impostor syndrome and skills-based hiring

Do you ever have that moment where you think, “oh no, I have so many responsibilities, but I have no idea what I’m doing”? Afterward, everyone congratulates you for handling the situation well, but deep down you believe that you had little to do with its success.

Put simply, impostor syndrome is the belief that you do not deserve the recognition you have received. A person who suffers from impostor syndrome at work often minimizes or underestimates their own skills. They might believe that their achievements have been unearned and fear that they could be exposed as a pretender at any moment.

While the above description might sound extreme, it’s actually very common. A recent report by Indeed found that 58% of employees experience impostor syndrome at work.[4]

There are many reasons that a candidate might have developed impostor syndrome. Some people suffer from it their whole lives, perhaps as a symptom of a mental health issue such as depression. For others, it could be the result of a traumatic incident. For example:

A toxic work environment or an abusive boss

Sexual harassment

Violence

Discrimination such as sexism, racism, or ageism

Recent events like COVID-19 and the subsequent economic downturn

Past failures, such as losing your job or business during a recession

Accidents and injuries

What does impostor syndrome look like in a candidate?

Candidates with impostor syndrome often commit that age-old faux pas of minimizing their achievements. They may say things like:

“I can’t take full credit for that.”

“I know I don’t have much experience, but…”

“I’m not very good at…”

However, most of the time, it manifests itself more subtly. In addition, some candidates might be more likely to have impostor syndrome than others.

We’ve all heard the statistic that women often only apply to a role if they have 100% of the listed qualifications, while men apply if they have 60%. Further research by women’s leadership expert Tara Mohr found that the higher threshold for applications didn’t reflect women’s lack of confidence in their abilities,[5] but rather:

A lack of knowledge among women about how hiring processes really work – specifically, the fact that “required” qualifications are often negotiable

A fear of applying and failing, possibly due to the fact that women’s failures are remembered longer than men’s[6]

The Indeed study cited above did find that women suffer from impostor syndrome at nearly twice the rates of men.

Age can also be a factor: Indeed reports that 27% of Millennial respondents felt like frauds in the workplace, compared to just 3% of those 65 and above.

Imposter syndrome can also disproportionately affect people of color, who may be under the false assumption that they were hired purely due to a diversity initiative rather than their actual qualifications.

In addition to using tools like skills tests to accurately gauge candidates’ competency, it’s important to have a diverse panel of hiring decision-makers. By having more ethnicities, ages, genders, sexualities, and other identities represented on the panel, you can help reduce bias in the hiring process since they are less likely to interpret each candidate in the same way.

How impostor syndrome sabotages your hiring process

Impostor syndrome, when left unchecked, isn’t just an individual problem: It can have a negative impact on your hiring process and your workforce as a whole.

It not only prevents qualified candidates from applying in the first place, but it also means that the ones who do apply might not put their best foot forward when it comes to their applications.

They often leave out key skills from their CV on the basis that they’re “not good enough” and, as we’ve already covered, project a lack of confidence when it comes to the interview.

Even if you’re confident that impostor syndrome wouldn’t stop you from hiring a qualified candidate, it may stop you from getting the best out of them once they’re hired – we’ll get to that in a moment.

Many recruiters actually view impostor syndrome as an asset in an employee. Studies support the idea that people with a negative bias in self-evaluation are less satisfied with their performance than their peers with a positive bias, even when they perform comparably.

This dissatisfaction can push candidates with impostor syndrome to work harder and pursue growth more doggedly. It may also be true that candidates with impostor syndrome are more well-suited to roles involving cost or risk assessment.

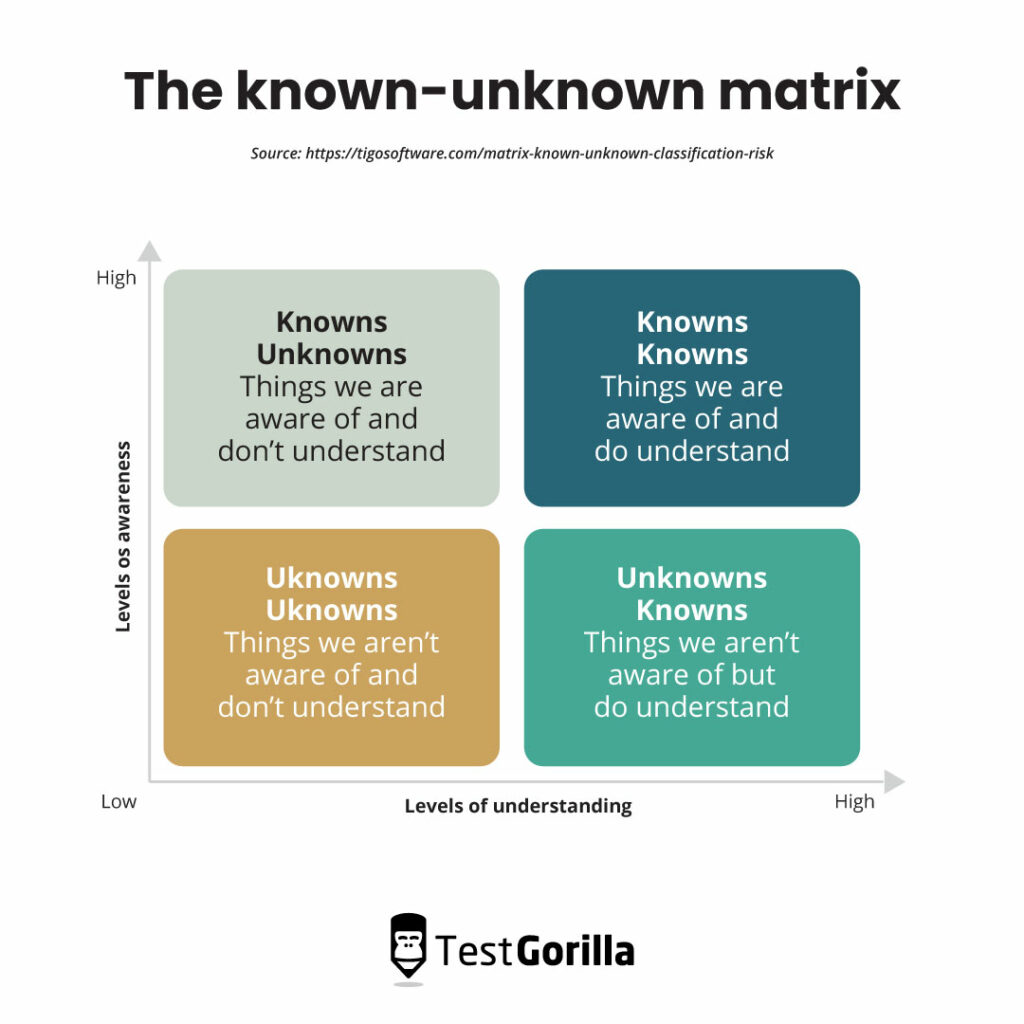

This is because of the known-unknown matrix that is often used to classify risk. A candidate with impostor syndrome is more keenly aware that there are “unknown unknowns” which could affect their projects – in other words, they don’t know what they don’t know.

Therefore, they might be on the lookout for learning opportunities and more open to testing and consultation than a more confident candidate who believes they already know everything.

However, this level of anxiety and fear of being “exposed” as a fraud means that impostor syndrome can lead to employee burnout.

Think back to the four archetypes of self-awareness we explored above.

With their high awareness of how other people perceive them and low confidence in their own abilities, employees with impostor syndrome fit into the “Pleasers” category. This may lead them to make decisions that ultimately work against their own interests and cause them to experience burnout.

Luckily, they’re not doomed. After all, confidence is something that is teachable with the right wellbeing initiatives.

Additionally, when you encourage an employee who is accustomed to seeking out growth and being critical of their own performance to validate their own skills, what you create is a highly valuable professional who still has an awareness of their limitations.

While employers can’t do much about impostor syndrome stopping people from applying for roles – except, perhaps, raising awareness that some aspects of a job ad can be negotiated or re-evaluated depending on the candidate – you can mitigate the negative effects of impostor syndrome for the candidates in your pipeline and nurture your employees.

How? The answer is simple.

Skills assessments see through impostor syndrome

As we’ve already covered, the requirement for self-evaluation leaves room for impostor syndrome to block good candidates from consideration in a traditional hiring process, but a skills-based hiring process limits this risk.

When you determine the essential skills for your open position and test all candidates for these skills, you prevent candidates with impostor syndrome from omitting certain skills from their application because they don’t feel they’re “good enough.”

You also give them the opportunity to show you what they can actually do, both in role-specific skills and in the general skills all employees should have, including:

Communication

Negotiation

Time management

Critical thinking

This improves not only the shortlisting process but also the interview itself. Before, you would have no way of knowing whether a candidate’s self-deprecation was an accurate depiction of their skills, but now skills tests give you the data to challenge their misconceptions.

For example, you might be able to respond: “You say that you’re not proficient in Google Ads, but you performed very well in our test. Could you explain what your personal benchmarks for success are in this area so I can better understand your skill level?”

Crucially, skills testing also streamlines the decision-making process by allowing you to measure the level of skill proficiency each candidate has and to stack this up in relation to other candidates – even the over-confident ones.

Those competitors present their own obstacles. It’s time to discuss the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

The best insights on HR and recruitment, delivered to your inbox.

Biweekly updates. No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

The Dunning-Kruger effect and skills-based hiring

The Dunning-Kruger Effect refers to a cognitive bias in which a person has excessive confidence in their abilities, but their actual skills don’t match up to their self-perception. It’s often presented as the polar opposite of impostor syndrome.

The term was first coined by David Dunning and Justin Kruger in a paper in 1999.[7] The pair of Cornell psychologists conducted a variety of tests, asking participants to predict how they would score on each one.

They found that the participants who scored in the bottom quartile on each test grossly overestimated their abilities, often predicting they would land around 50% higher than they actually did.

Some researchers have critiqued this term, suggesting that these findings show that most people regress to the mean when asked to rate their own performance. When asked how they’ll score on a test they’ve not completed before, they argue, people tend to guess that they’ll do slightly better than average.

However, it’s hard to argue that overconfidence doesn’t exist in business.

For an example of this effect in action, look no further than Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter. Prior to his hastily planned purchase of the site, Musk had no experience in managing a social media platform.

After claiming that his leadership would reduce harmful impersonations on the platform, Musk fired much of the Twitter staff and rushed through a paid verification process whereby users could purchase the famous “blue tick” for $8 a month. While $96 a year is pretty steep for a premium social media account, people were more than willing to pay $8 for a few pranks.

Needless to say, his efforts backfired. The impersonations of corporate accounts on the platform skyrocketed, wreaking havoc on businesses. Pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly saw their share prices drop after a hoax tweet went viral, prompting them to suspend all ad spending on the platform.

This was a huge blow for Twitter’s finances – and a cautionary tale of what can happen when a Dunning-Kruger candidate flies too close to the sun.

What does the Dunning-Kruger effect look like in a candidate?

Here’s the difficulty with spotting the Dunning-Kruger effect in a candidate: Applicants are encouraged to present as much confidence as possible to interviewers. They are encouraged to take as much responsibility as possible for their successes and exaggerate their level of confidence in their skills.

So how can you tell the candidate whose confidence is merited from the one whose ability is being exaggerated – especially as the Dunning-Kruger effect means that they don’t realize they’re doing it?

In a traditional hiring process, there are very few tools to help you with this task. Because of this, recruiters frequently fall back on years of experience as a qualifier, but research suggests that experience is not the safe bet it seems to be.

One study found that although a lifetime of experience makes leaders more decisive, it does not necessarily make their decisions more accurate. Rather than constantly recalibrating their decision-making, leaders with many years of experience are more likely to assume they know what they’re talking about and demonstrate false confidence.[8]

We think looking at a candidate’s length of experience in a field should be a prompt to probe further into their history, not a dealmaker in and of itself.

For instance, if a candidate says they are “highly skilled” in an area they’ve only worked in for a short time, you might reasonably question them further about how they have developed skills in such a short time and what evidence they have of their improvement.

On the other extreme, it may be valuable to ask someone with many years of experience how strongly that experience benefits them. How have their skills and perspective regarding the job changed over time? Find out if their experience was a time of growth or a time of career stagnation.

How the Dunning-Kruger effect damages your business

Most hiring managers have been burned at one time or another by a disappointing hire who they thought was going to revolutionize their team but ended up being unprepared for the role.

This mistake usually starts in the hiring process. We all think that we’re good at spotting excessive confidence. In fact, 65% of recruiters say they find arrogance to be a turn-off in interviews.

However, a 2014 study found that observers largely take people’s abilities at their word: Overconfident individuals were overrated by observers, while underconfident individuals were thought to be worse than they actually were.[9]

Once granted entry to your business, any number of issues could ensue.

Let’s take a look back at the known-unknown matrix again. A candidate affected by the Dunning-Kruger effect is less likely to be aware that there are things they don’t know when entering a new project – those “unknown unknowns.”

To them, they may believe that an idea is clever or correct simply out of the notion that they were the person who came up with it. This lack of interest in planning or testing could backfire, as indeed we’ve seen in the case of Elon Musk.

The same issue might make them less likely to create or engage with personal development goals, which limits their growth potential. After all, the number of skills required by a single job is increasing by 10% year-on-year, so it’s important to hire candidates who are eager to upskill.

Another difficulty is that, while confidence is teachable, humbling an employee who thinks that they deserve more credit than they’re getting can lead to unwanted workplace conflict.

Developing a Dunning-Kruger employee requires a careful hand, and if neglected, they might feel isolated and underappreciated. If we look back at the archetypes of self-awareness, we might categorize Dunning-Kruger hires as “Introspectors,” who are at risk of having poor relationships and hitting a “ceiling” when it comes to success.

All of this is not to say that confidence in itself is a red flag in a candidate. Many professionals have a solid foundation of feedback and demonstrable achievement on which they base their confidence.

But confidence alone is not a perfect indicator of a candidate’s skill level, and you should always check it against hard data. That’s where skills-based hiring comes in.

Using skills-based hiring to identify Dunning-Kruger candidates

The ability of skills-based hiring to assess what someone’s actual skill level is (and not just what they say it is) can help you sort the justly confident candidate from the arrogant. It also allows you to test their core competencies for the role rather than being dazzled by their proficiency in secondary skills like presentation and communication.

Skills testing lets you compare these candidates’ results to those of their competitors and make a balanced decision. It’s particularly effective when used in combination with a structured interview approach.

Put simply, a structured interview approach requires that you ask every candidate the same questions in the same order. In a final interview, you might therefore choose to ask every candidate the same question, targeting their self-awareness.

For instance, Emma Brudner, director of people at Lola.com, recommends that all recruiters ask candidates the following question to test self-awareness: “Think of someone you didn’t jibe with at work. How do you think that person would describe you?”

This question requires candidates to demonstrate:

External awareness, of how they are perceived by others

Internal awareness, to assess how this aligns with who they feel they “really are”

Empathy, to put themselves in another person’s shoes

Humility, to understand the parts of their personality that might not sit well with other people

True confidence, to present this more negative assessment to a potential employer with the knowledge that it doesn’t mean they’re not qualified for the role at hand

Use a skills-based approach to make (and develop!) great hires

A skills-based approach can help you stop candidates and hiring managers alike from getting in each other’s way during the hiring process and give you confidence – true confidence, this time – in the abilities of the people you hire.

To get started, you can use skills testing to screen candidates based on important skills such as communication.

You can also use a skills-based approach to develop candidates once they become employees.

As we mentioned above, identifying candidates whose confidence in their own skills is lacking should be a sign for your business to nurture them. Use tests to help you validate employees’ skills and demonstrate their proficiency with hard data, while also identifying areas for potential growth.

To find out more about this process, read our blog about upskilling employees, or to get a broader overview of nurturing employees’ skills, check out our guide to learning and development.

Sources

Guillen, Laura. “Is the Confidence Gap Between Men and Women a Myth?” (March 26, 2018). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved February 06, 2023. https://hbr.org/2018/03/is-the-confidence-gap-between-men-and-women-a-myth

Eurich, Tasha. “What Self-Awareness Really Is (and How to Cultivate It)”. (January 04, 2018). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved February 06, 2023. https://hbr.org/2018/01/what-self-awareness-really-is-and-how-to-cultivate-it

“2018 Student Developer Report”. (2018). HackerRank. Retrieved February 06, 2023. https://www.hackerrank.com/research/student-developer/2018

“Working on wellbeing: Mental health and wellness in the UK workplace. 2022 report”. (May 8, 2022). Indeed for Employers. Retrieved February 06, 2023. https://uk.indeed.com/lead/working-on-wellbeing-2022-report

Mohr, Tara Sophia. “Why Women Don’t Apply for Jobs Unless They’re 100% Qualified”. (August 25, 2014). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved February 06, 2023. https://hbr.org/2014/08/why-women-dont-apply-for-jobs-unless-theyre-100-qualified

“What works for women at work”. (February 03, 2014). Stanford The Clayman Institute for Gender and Research. Retrieved February 06, 2023. https://gender.stanford.edu/news/what-works-women-work

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. “Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments.” (1999). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.112

Prims, Julia P, and Don A Moore. “Overconfidence over the lifespan.” (January 2017). Judgment and decision making vol. 12,1. Retrieved February 06, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5978695/

Lamba, Shakti and Vivek Nityananda. “Self-Deceived Individuals Are Better at Deceiving Others”. (August 27, 2014). Plos One. Retrieved February 06, 2023. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0104562

You've scrolled this far

Why not try TestGorilla for free, and see what happens when you put skills first.